Old tax lists of Tredyffrin township are warrant for the belief that between 1765 and 1767 there “was established by Jacob Sharraden, what seems a distinctive feature of German Protestant settlements – a place for church and school purposes; and that he was the donor, at least of the ground on which it was located.” This is the conclusion to which Henry Pleasants came in his exhaustive study of the early German settlers around Strafford when he was preparing to write his “History of the Old Eagle School”.

Mr. Pleasants’ study of early records and of traditions led him to believe that there was considerable rivalry between this early German congregation and the Welsh one that centered around

old St. David’s Church.

“It was possible,” Mr. Pleasants writes, “that the establishment of the Lutheran settlement near “The Eagle” had aroused the church members of old St. David’s Church, Radnor, from their temporal, if not their spiritual, apathy by an apprehension lest these Lutherans should develop into formidable rivals who might draw away support from their own church”. At any rate these Welshmen seem “to have been spurred on to increase their accommodations and conveniences at Radnor”.

“It was possible,” Mr. Pleasants writes, “that the establishment of the Lutheran settlement near “The Eagle” had aroused the church members of old St. David’s Church, Radnor, from their temporal, if not their spiritual, apathy by an apprehension lest these Lutherans should develop into formidable rivals who might draw away support from their own church”. At any rate these Welshmen seem “to have been spurred on to increase their accommodations and conveniences at Radnor”.

Tradition has it that the rigorous religious tenets of these first German settlers made it difficult to obtain additions to the membership of the first small log church. Apparently the old members removed to more congenial surroundings, and before their departure the combined church and school property was transferred to “a few chosen representatives of the neighborhood as trustees, who were to hold it for religious and educational purposes and the re- pose of the dead.” Jacob Sharraden, who had given the original acre of land on which the first little log building stood, was among them, moving from Tredyffrin township to Vincent township in 1771.

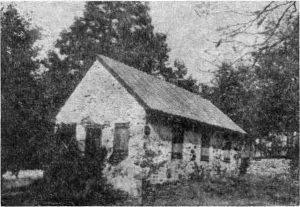

It was probably in the year 1788 that the stone building, used for school purposes alone, was built, a date that is substantiated by the large stone now high in the south gable. It is held that the two structures stood side by side until 1805, when the log one was demolished.

Some of the massive logs are said to have been utilized in the construction of the old Hazzard house about a half mile north of the School House. Still later these same logs were used in the house built by the late Murdoch Kendrick, Esq., at the corner of Eagle and Gulph roads, and still occupied

by Mrs. Kendrick.

Regarding the erection of the stone building in 1788, there is a meager record. The residents of the neighborhood united to furnish the necessary masonry and carpentry work as well as the materials. Among these pioneer philanthropists were John Pugh, William Siter and Robert Kennedy, of Radnor, and Jacob Hazzard and Robert Grover, of Tredyffrin.

In 1842, six years after the common school system of Pennsylvania came into full operation, the school boards under the new system succeeded the trustees in the management of the property. This probably was the main cause for the renovation of the small structure in 1842. It provided for the addition of the southeasterly end, which about doubled the school’s capacity. At this time the old door was walled up and an entrance made from the southeast end.

The reminiscences of the three early pupils of the old Eagle School, Margaret Cornog, Joseph Levis Worrall and Joseph Fisher Mullen, as given in this column in September and October, 1952, were of the period previous to this renovation, while the school was still very small.

During the period of the Civil War, the building continued to be used as a schoolhouse, but by 1872 the School Board of Tredyffrin township had completed the erection of a new schoolhouse at Pechin’s Corner, about a quarter of a mile northwest of the Eagle School. As the only badge of ownership, the key to the old building was presented to the little Union Sunday School, then holding weekly services there. During the year 1873, the Sunday School organization was the only custodian of the property, and apparently there was no prohibition here against denomination.

It is said that the building from time to time was used by preachers from the Christian Church, by Baptists, Presbyterians, Episcopalians and possibly Quakers. The last Sunday School service was held on October 12, 1873, when the School closed its sessions for the winter. For a few weeks previous, teachers of the Sunday School had brought with them supplies of wood and of coal from which they built their fires.

Just before the usual time for reopening the Union Sunday School in the spring of 1874, a well-known colored man of the neighborhood took possession of the small building as a dwelling for his family, claiming that its use was given him in return for his care of the graves in the surrounding churchyard. Much litigation ensued, finally ending in a fruitless attempt by the school board, to dispose of the

Just before the usual time for reopening the Union Sunday School in the spring of 1874, a well-known colored man of the neighborhood took possession of the small building as a dwelling for his family, claiming that its use was given him in return for his care of the graves in the surrounding churchyard. Much litigation ensued, finally ending in a fruitless attempt by the school board, to dispose of the

property through a sale.

When they found that they could not sell property, the Board rented the building to one Elizabeth Dickensheet, who was better known as “Chicken Lizzie” because of the “members of the feathered tribe who shared her home”. The appearance of squalor and dilapidation which the whole property, including the graveyard, presented at this time was shameful. The occupation of the old building as a dwelling terminated after “Chicken Lizzie” was set upon by someone whose identity was never discovered.

In May, 1885, a formal decree was entered, appointing Thomas R. Jaquette, Elijah Wilds, John S. Angle, M.D., Daniel S. Newhall and Henry Pleasants, as trustees. From this group Mr. Wilds was named president and Mr. Pleasants, secretary and treasurer.

Funds to meet the preliminary expenses of restoration were obtained by contributions from interested neighbors and also from the sale of an historical account of the old school, as prepared by the secretary, Mr. Pleasants.

The restored building is described by the ”Evening Bulletin” of September, 1897, as “quaint and venerable looking… with painted walls, shadowed by many fine old trees. A Colonial doorway and low cornice suggest a history co-extensive with the nation, and the inscription, 1788, in quaint lettering on the old date stone, high in the south gable, confirms the suggestion.”

During 1897-1898 further improvements were made by excavating a cellar under the entire building, by grading the reclaimed road bed, and by enclosing, with stone walls, that part lying west of the graveyard, along with many other extensive outside changes to the grounds.

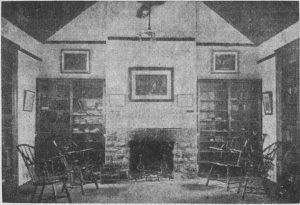

The first picture shown this week was made expressly for this column by F. G. Farrell and shows the school building as it looks today. The second picture is from an illustration in Mr. Pleasants’ book, showing the interior of the schoolhouse after its renovation in the late 1800’s.

(to be concluded)