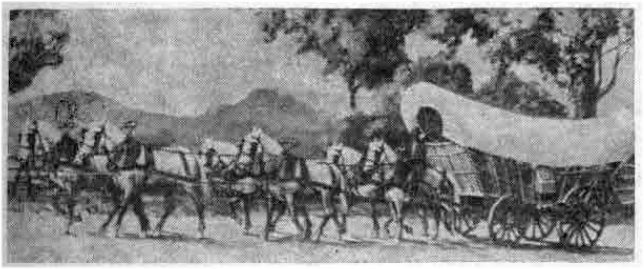

Illustrating this column in last week’s issue of “The Suburban” was a picture of a typical Conestoga wagon with its six-horse bell team. Wagon and team were the property of Jacob Eby, of Chambersburg, great-grandfather of Mrs. Norman H. Dutton, of North Wayne avenue, who kindly leant your columnist the picture for use in this series on Conestoga wagons. The original of the picture was one taken of Mr. Eby in 1843, as he made one of his many trips between Pittsburgh and Baltimore.

Among the appurtenances of such a wagon were the tool box and “lazy Board” which show plainly in the picture. These were described in last week’s column, as were the tar box and wagon jack. Swinging from the back of the wagon was the large feed box for the horses, a very necessary adjunct to a lengthy trip.

These boxes were usually longer than the wagons were wide and had their special place at the rear end. Here one would hang “like a bustle, sheltered by a projecting cover”, to quote John Omwake’s description in his book, “Conestoga Six-Horse Bell Teams.” A travelling farmer usually carried his own feed, while the professional wagoner bought his wherever he stopped.

The water bucket hung at the rear axletree on the pole, or on the side of wagon bed. At night the horses slept outdoors on their bedding of straw, while in the meantime, as Mr. Omwake writes, “their drivers boasted of them in the barroom of the inn.” The wagoners themselves usually slept around the stove in the barroom of the inn, using their own blankets and mattresses.

Of the general construction of these Conestoga wagons, H.K. Landis, of the Landis Valley Museum in Lancaster, who collaborated with Mr. Omwake in the latter’s book, says that “long before the wagon was ordered the wheelwright had gone into the forest and selected trees that would serve his purpose; white oak for the framing, gum for the hubs, hickory for the axletrees and singletrees, and poplar for the boards.

“Since the wooden parts of the wagon were made as light as practicable, the wood had to be strong as possible, and no knots, checks, soft spots or unseasoned wood was permitted. The material and design of the wagon made it unbreakable under the trying conditions met on road full of rocks and ruts, and sometimes stumps and roots; on corduroy and log road, through swamps, and on side hill roads that put a severe strain on the wheels on one side.”

And because “with the wheels, the wagon stands or falls”, these wheels were made even stronger than would appear necessary. Spokes were split from straight white oak and worked down with a hand axe, placed in a vise and further shaped with a draw knife and finished with a spoke shave, according to Mr. Landis. The hub, which was fashioned from black or sour gum, was “turned on a lathe and cored to receive the axle… the mortices were exactly placed and made so that the spokes had to be driven into them with powerful blows of the maul or sledge… wagon tires were made of iron by a hand process that was both tedious and difficult. Axle and axle tree were of white oak or hickory, the strongest wood available.”

When the long and difficult construction of the wagon was completed, it was painted in such a way as to be both picturesque and impressive. Wheels and removable side boards were a bright red, while the running gear was a soft blue with the white of the hempen wagon cover setting both colors. The uniformity of this painting for all Conestoga wagons was perhaps due to the fact that in those days few colors were available.

For their red, the wagon makers dug up the firm red lead, placed it on the rubbing stone with good linseed oil and rubbed it until it was smooth. Prussian blue also came in solid form and had to be ground in oil. “But when put on, these paints stuck”, as Mr. Landis tersely expresses it.

Covers for the wagons were about 24 feet long and made of white homespun. A picture of the inside of one shows the “turn-in” at either end, to allow the draw string to give the right shape to the openings. This cover “fitted over board hickory hoops, fastened into iron sockets or staples on the outside of the body. The lowest bows were midway between the ends, and the others rose gradually in a deep curve to front and rear, so that the ends were of nearly equal height. The cover was corded on the sides and drawn together by draw ropes at the ends, so that the wagon was almost closed in.

Harness or “gears” as it was called by the wagoners, was made of leather that had been bark tanned, the work done by hand, and the process requiring from eight to ten months. Leather cured in this way never lost its life and softness. Bridles were entirely of flat leather, and blinders were made of single pieces of leather and unstiffened. The drivers used only one line to control the lead horse, which in turn controlled the whole team by means of a “jockey” stick, a thin piece of seasoned hickory wood fastened to the hames of the lead horse and to the bit of his mate, the off horse.

In the research for today’s column the writer has made the interesting discovery that Mr. Omwake knew David Eby and consulted him in regard to the trips the latter had made by Conestoga wagon. Mr Omwake writes that “by far the greatest number of stories of the old wagon deal with the later days on the road to the West. Of all of these, none is more vivid and delightful than that written by David Eby.” And it was Mr. Eby’s granddaughter, Mrs. Dutton of Wayne, – until this time a stranger to the writer – who telephoned and offered her the picture of the wagon used by her great-grandfather as well as her grandfather.

Another interesting keepsake in the possession of the Dutton family is a small, hand-bound booklet, containing the specifications for the making of Dearborns. The booklet belonged to Joseph F. Hill, Mr. Dutton’s geat uncle, who was a carriage maker more than 100 years ago, the date in the front of the booklet being June 29, 1841.