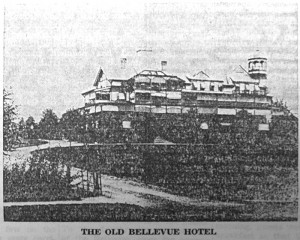

The night of March 15, 1900, was one of intense excitement in Wayne, as many old timers now recall it. An unseasonably late snowstorm blanketed the countryside. The ice-coated branches of the trees creaked under their own weight as they bend and tossed in the high wind. Icicles hung from the eaves of all the buildings. A more terrifying setting for a fire can scarcely be imagined. Small wonder that on such a night as this, a fire, once under way, should totally destroy the Bellevue Hotel, as it stood on its high eminence on West Lancaster avenue.

A large group of Wayne’s young people had been to the opera that night in Philadelphia, and had returned home with some difficulty, on one of the late trains from the city. Among these were several members of the Wood household, who were shortly roused from their first deep sleep by a pounding on the front door, so loud that it resounded even above the noises of the storm. A Pennsylvania Railroad watchman, patrolling the tracks, was unable to find the doorbell in his confusion over discovering that a fire was well under way in the summer hotel adjoining the Wood property on the west. The entire household responded to his call and an alarm was immediately turned in to the face of almost overwhelming odds, the fire-horse dragging the heavy apparatus with difficulty through the deep ice-encrusted snow.

Mrs. Charles H. Stewart and Mrs. F. Allen McCurdy still recall the scene clearly as they watched it from their windows throughout the dark hours of the early morning of March 16.

In the midst of the intense excitement their mother, Mrs. Wood, quietly put on her warm winter coat and braved the elements in order to supervise the removal of the horses from the stable standing near the boundary line between the two properties. Not only were they all blanketed, but in order to avoid panic, each horse was carefully blindfolded as he was led from the stable.

Being constructed entirely of stone, the building was not destroyed in spite of its close proximity to the fire. Mrs. McCurdy says that when she moved from the old homestead only a few years ago, there was still one reminder of the fire in the form of a window in the hayloft that had been cracked by the intense heat of the flames but had never been replaced.

Had it not been for the deep snow, the high wind might have caused a holocaust in Wayne. As it was, burning embers were blown in all directions, some of them still smouldering when daylight came.

A resident of North Wayne still recalls his father’s fear that their Walnut avenue home might catch fire from the embers that were being blown that far in the high wind. Albert Ware, who lived with his family on West Wayne avenue, remembers watching the family coachman attach a long garden hose to an inside faucet, then pull it upstairs, under Mr. Ware’s direction, to a third floor window that gave access tot he roof. From this vantage point he stood ready to direct water on any fling embers that might land on the roof. Albert Ware remembers, too, how clearly the fire was visible from his window, and he watched the hotel burn to the ground.

Among others who lived on West Wayne avenue at the time of the fire, and still reside there, are Miss Mary Allen and her sister, Mrs. Henry Conkle, both recalling vividly the night of March 15, 1900.

According to all spectators, the entire sky was lighted up by the blaze. Mrs. W. Stanford Hilton, then Frances Wood, watched the scene as she stood in one of the front windows of the family home where she still lives, on the southeast corner of Windermere and Audubon avenues. With the present tall trees then in their early stage of growth, there was little to obstruct her view. When the cupola on top of the hotel caught fire, she could see it clearly as it broke loose from the main structure and rolled over and over down the snow-encrusted hill to the Pike.

Among those who really had front seats for the fire was the J. M. Fronefield family who then lived at 116 West Lancaster avenue. Joe Fronefield still recalls the thrill of the very small boy who watched his first big fire, cozily wrapped up in a blanket at one of the front windows of his home! Miss Helen Lienhardt also recalls watching the blaze from her house, as the firemen made their difficult and perilous way through the deep snow. The next day she joined other children in collecting in paper bags choice and long-cherished souvenirs of the fire.

The William Henry Roberts family were just then moving to the home on Windermere avenue still occupied by several of their members. With all their household goods in a freight car on a siding at Wayne Station, they were spending the night of the fire at the home of the J. Donaldson Paxtons who lived then on East Lancaster avenue.

Suddenly roused from her sleep by the shrill blowing of whistles, Miss Grace Roberts recalls that the sky was so light that she thought it must be morning, and she wondered vaguely if, in their new home town, they would always be wakened in this manner! As they roused more fully, the family began to realize that with the Bellevue so close to the railroad station, their furniture was in danger of being destroyed. However, Henry Roberts recalls that he found some consolation in the the thought that if the furniture burned up where it was, it would not have to be unloaded and unpacked! Miss Roberts also remembers that the snow was so deep that they went on bobsleds to Windermere avenue!

And so, through the eyes of some of our fellow townsmen who were living in Wayne in 1900, we can reconstruct the scene of perhaps the largest and most spectacular fire Wayne has ever experienced.

The Bellevue Hotel, so famous in its picturesque luxury throughout the brief nineteen years of its existence, is but a legend now. But it too has momentarily been brought vividly to life for us by a brother and sister who spent ten years of their childhood there when the Bellevue was in its heydey. To Dr. George w. Arms, of Lansdowne, and to his sister, Mrs. Horace J. Davis, of Wallingford, this columnist wishes to express her gratitude for the information which has made this story of the Bellevue possible. And to her fellow townsmen who have recalled such vivid incidents of the night of the big fire, Mrs. Patterson is also grateful.

(The End)