The Late-19th Century Establishment of St. Mary’s Episcopal Parish, Wayne, And the Building of its Memorial Church

by Roger D. Thorne

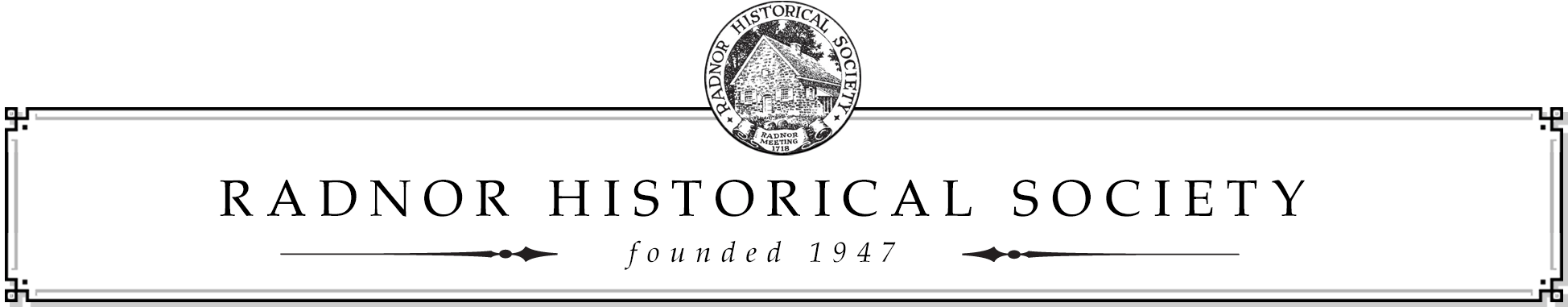

In a community abundant with comely architecture and design, one of the most stately properties in Wayne, Pennsylvania is that comprising the parish of Saint Mary’s Episcopal Church. Located on the corner of Lancaster and Louella avenues, in the midst of the Downtown Wayne National Register Historic District, it was designed in an English-inspired Parish Church style. The church has been commended by the Radnor Historical Society as “an integral part of Wayne’s core and historic architecture.”

We will explore the late 19th century establishment of this architectural gem, and the proximity and convergence of three exceptional individuals principally responsible for the creation of St. Mary’s.

I.

The Turnpike which connected the cities of Philadelphia and Lancaster had passed through Radnor Township since 1794. And in its heyday, its first forty years, it was a marvel. This turnpike, “the first artificial road of crushed stone and gravel in America,” 1 had allowed overland commerce on a heretofore unimagined scale.

The sheer volume of passengers and freight traffic generated by the road changed the route itself. Numerous inns and taverns were established to serve the various needs of both travelers and stock, and around these hostelries, small villages or hamlets developed as blacksmiths, wheelwrights, and other businesses were established to serve the wagons and coaches and other vehicles traveling the pike.

At the extreme eastern edge of Tredyffrin Township, Chester County, the eastbound Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike was intersected by the original Lancaster Road (closely following today’s Conestoga Road), where they together carried their combined traffic into western Radnor Township, Delaware County through a loose settlement first called Spread Eagle. As the small village grew around the crossroads of the Turnpike and Valley (now Old Eagle School) Road, the name changed to Siterville around 1807 (named after its most prominent resident, Edward Siter).2

The heart of that community was the Spread Eagle Tavern, originally licensed in 1764, and standing on the north side of the original Lancaster Road in west Radnor Township (on land today comprising a cluster of specialty shops called “Eagle Village Shops.”) With the increased traffic on the new Turnpike, the Siter family built an imposing three and a half story replacement to the old inn and tavern in 1798. This new larger structure, with dimensions of 80 by 33 feet, quickly gained a stellar reputation for both service and amenities, and was considered, along with the Paoli Inn, one of the very finest hostelries along the entire 62-mile turnpike. The Spread Eagle was especially favored by the elite stagecoach clientele.

But after four decades, the demise of the Turnpike began in earnest. By April 1834, the world’s longest double-tracked railroad, officially designated “The Philadelphia & Columbia Division of the Pennsylvania Railroad,” 3 was regularly carrying passengers and freight across the 82 miles between the Schuylkill and Susquehanna rivers. The almost ceaseless, decades-long flow of commerce upon the Turnpike was now increasingly diminished as more and more travelers and goods could more conveniently and cheaply be transported by rail. And thus the reduction of toll revenues meant the road could not be properly maintained, and deterioration on this once-pristine roadway was soon significant. Increasingly, inns and taverns along the Turnpike began to close in this reversal of fortune.

By 1880, the year the Philadelphia partnership of publisher George W. Childs and financier Anthony J. Drexel purchased the 300 acres of J. Henry Askin’s “Louella” in their first step to create an innovative community called “Wayne Estate,” the old Turnpike was pitted and forlorn as it passed through Radnor Township.

But the promise of improvement was imminent. In April 1880 the Lancaster Avenue Improvement Company, under the leadership of its president Alexander J. Cassatt, completed the purchase of the easternmost 19 mile section of the old Turnpike extending from Philadelphia to Paoli. By May 1881 the worn out “Pike” had been thoroughly “macadamized” from Philadelphia west through Bryn Mawr, and was now described as “a splendid driving road.” The Company predicted that the final nine miles through Radnor to Paoli would be completed by “next fall.” 4

And what about the 1798 Spread Eagle Tavern? In recent years the old inn, standing just 0.8 miles west of central Wayne, had “become a tenement house, with as many as five and six families at a time being quartered in its commodious rooms and halls.” 5 The structure had then stood vacant for three years and was beginning to show significant evidence of dereliction. In 1881 the Spread Eagle and its surrounding property were purchased by partners George W. Childs and Anthony J. Drexel to prevent anyone from buying it and obtaining a license to sell liquor so near their new development of Wayne Estate.6

II.

Mary McHenry Cox was a woman both compassionate and formidable. Born in 1827 and left with a substantial fortune, young Mary McHenry had by February 1856 created a charitable organization in Philadelphia called the “Church Home for Children,” which she ran out of her home at 1902 Chestnut Street to house and educate “friendless children” (orphans). Within a decade the Civil War had created desolation for countless families across the nation, and she adapted the mission of her Home to house and educate 100 boys, aged 12-21, who had been orphaned by the deaths of their soldier-fathers.

This new charity was chartered as the Lincoln Institution on May 9th, 1866, exactly one year after the end of the Civil War. Miss McHenry solicited the funds necessary to acquire and adapt a large mansion at 324 South 11th Street, Philadelphia wherein “her boys” could reside while completing apprenticeships enabling them to support themselves. Her efforts to help military orphans continued until 1882, by which time there were few Civil War orphans young enough to qualify for the Institution.

It was in that year of 1882 that Mary McHenry Cox (she had since married the prominent Philadelphia attorney John Bellangee Cox) was first introduced to the work of the United States Indian School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and to its founder and superintendent, Captain Richard Henry Pratt. The Carlisle Indian Training School had been founded just three years before in 1879, the first government off-reservation Indian boarding school in the United States. Its mission, however controversial by today’s perceptions, was to create opportunities for Native American children through assimilation to prepare them for success in America’s mainstream culture. The Carlisle School was the precursor for over 300 such boarding schools for Indian children in the United States over the next 40 years, including Philadelphia’s Lincoln Institution, of which Mrs. Cox was president.

Mary McHenry Cox was energized with the importance, and the rightness, of her challenge, reflecting:

“The Government has opened schools on the reservations, and Missionaries have gone out to them, but this does not answer the need. Their reservations are [still] all Indian. … [and] our strong hand withholds from them participation in our wider life … To effectually civilize the Indian … he should be subjected to the broadest cosmopolitan influences.”

In short, the aim of her school was to teach these children both “the duties of civilization and the beauties of religion.”

In its first year as an Indian School, only girls were invited to attend the Lincoln Institution. The first group, all from reservations of the Sioux nation in the Great Plains, arrived at 324 South 11th Street in Philadelphia on September 8, 1883 – at what was now referred to as the Girls’ Home of the Lincoln Institution. By the following spring of 1884, the school had a total of 84 girls in attendance, most between the ages of ten and fourteen, and from fourteen different Indian nations from New York to California. Half of each day was spent attending classes on reading, penmanship, grammar, and music, with the other half receiving instruction in baking and cooking, housework, and sewing.

III.

At the beginning of the 1880’s, it was later recalled that:

“… there were few houses in Wayne. The Louella Mansion, the old [Radnor] Baptist Church which stood on the corner of Conestoga road and West Wayne avenue, the old Presbyterian Church on the Lancaster pike, the Masonic or Lyceum Hall on the corner of the Turnpike and Wayne avenue, and eight or ten houses on Bloomingdale avenue — these, with a few scattered houses on farms, formed the nucleus of the new town of Wayne.” 8

But Childs & Drexel’s community was growing in large part due to the tremendous improvements made on its right of way by the Pennsylvania Railroad. Easy and reliable rail access from Philadelphia had been increasingly attracting summer visitors after the Philadelphia Centennial Celebration in 1876. A growing number of these visitors were deciding to build “summer cottages” in and around Radnor Township, including Mary and John Cox. In 1883 the Cox’s purchased a 15-acre estate which they called “Ivy Croft,” just north of Wayne in Tredyffrin Township, Chester County, near the intersection of Upper Gulph and Radnor roads. The Cox’s quickly became socially well established in the developing community formerly known as Louella, and enjoyed a cordial friendship with Wayne Estate co-founder George W. Childs.

IV.

George W. Childs (1829-1894) was a publishing magnate, editor and co-owner of Philadelphia’s Daily Ledger, a social visionary, and the lifelong friend and business partner of internationally-renowned banker and financier Anthony J. Drexel. Born of very modest means in Baltimore, he moved to Philadelphia at the age of fourteen to work for a bookseller. By eighteen he had gone into business for himself. In 1849, at age 21, Childs joined the small Philadelphia publishing house of R. E. Peterson & Company. Five years later, in 1854, owner Robert Evans Peterson (1812-1869) invited George Childs to become a full partner with him in what became known as Childs & Peterson Publishing Company. These two partners seemed well-suited to one another, and the firm thrived. (Robert Evans Peterson would later became George W. Childs father-in-law when Childs married Peterson’s daughter Emma). In 1864, after Peterson had retired from publishing, Childs purchased the struggling Public Ledger with the help of his friend Anthony J. Drexel as a silent partner. George W. Childs turned the Public Ledger into one of Philadelphia’s eminent newspapers – and Childs into the top tier of America’s millionaires.

But a pamphlet published in 1870 by James Parton, a lifelong friend of Childs, reveals the true heart of the man. In George W. Childs: A Biographical Sketch, Parton recalls a letter which he received from his friend George when they were boys: “… he wrote to me years ago … that he meant to prove that ‘a man could be liberal and successful at the same time.’” 9 Childs became one of the great philanthropists in the country during the late 19th century, and it may be that his generosity is the primary attribute for which George W. Childs is still remembered today.

V.

Early in 1884, with her first class of Indian girls more than halfway through their academic year, Mary McHenry Cox and her staff were growing increasingly concerned about the Institution’s summer session. How would her Indian girls deal with the potential ill-effects of the humid Philadelphia summer, and the threat of disease so prevalent which could prove disastrous for some or many.

Mary, who with husband John was already we acquainted with George W. Childs within their social circle, called on Mr. Childs to discuss an idea. Would Mr. Childs be willing to allow the deserted Spread Eagle Tavern, purchased by Childs & Drexel in 1881, to be used as a summer venue for her Indian School? It is not known how much Childs initially knew about the School, but his response was immediate … and characteristically generous.

Childs and Drexel had no particular plans for the Spread Eagle, and agreed to make the property available to the Institution for use that summer without any rental or lease assessments. There was, however, considerable work needed to refurbish the old stone inn, and these expenses would be borne fully by the Institution. It was reported that the school incurred an expense of “over a thousand dollars” (some $30,000 in 2020 dollars) to make the building safe, habitable and usable as a school. 10

The work of thorough cleaning, whitewashing and painting the interior rooms, laying new flooring, replacing the many broken windows and other repairs, was started in April 1884. Under the personal supervision of Mrs. Cox, the work was completed by Thursday, May 29th, just in time for the arrival into Wayne of her 84 Indian girls aboard two special Pennsylvania Railroad coaches from Philadelphia (and with the expectation of an additional sixteen students that would soon bring the full enrollment to 100). Accompanying the girls were 12 employees and teachers from the Institution, as well as the Rev. Joseph L. Miller, an Episcopal clergyman from Mt. Airy, who would reside at the summer school while serving as its chaplain. Also supporting the Indian school at the Spread Eagle was a popular local physician, 28-year-old Dr. Joseph C. Egbert, M.D., whom Mrs. Cox had specially requested to provide his services as the school’s physician. 11

On Sunday, June 1, 1884, three days after the arrival of the students and staff to their summer location, the girls, most of whom had been baptized into the Episcopal Church, took part in their first church service conducted by Rev. Miller. The service was held at the Lyceum Hall, one of the most important buildings in Wayne, through the generosity of Mr. Childs who allowed the school to use the Hall for divine services each Sunday during the summer, as well as for special occasions. It was reported that the Hall had been decorated “into quite a pretty chapel” by gifts from various people interested in “this branch of the work of civilizing and improving the condition of the Indians.” 12 Members of the community were cordially welcomed to attend these Episcopal services, and as the summer progressed, local attendance grew.

Over the summer of 1884, the Lincoln Institution’s Philadelphia building at 324 South 11th Street, designated the Girls’ Home, was augmented by a second facility opened some three miles across the city at South 49th Street and Greenway Avenue, referred to as the Boys’ Home, The rhythm of education at the Spread Eagle had meanwhile continued throughout the summer until the girls were ready to return to Philadelphia late in September to resume their normal classes. This first summer session had been a great success, and plans for a return to the old Spread Eagle the following summer of 1885 soon began.

VI.

If one was an Episcopalian living in Wayne in 1885, proximity to a nearby parish where one could practice the familiar liturgies of the faith was not ideal. The nearest Protestant Episcopal churches were St. Martin’s Church in Radnor, Old St. David’s Church-Radnor, and the Church of the Good Shepherd (then meeting in Villa Nova). While none of these parishes were far distant from Wayne, the slower methods of travel available, especially in cold and inclement weather, would deprive many church people the possibility of regular attendance. So when the Indian School again returned during the summer of 1885, and Fr. Miller again led Episcopalian services in the Lyceum Hall, it is recorded that a steadily increasing number of townsfolk began to join with the Indian girls to worship each Sunday. George W. Childs was a lifelong Episcopalian, and a vestryman at his home parish of St. James Church in southwest Philadelphia. His background assuredly influenced his decision to help the Indian School with its use of the Lyceum, as well as with future Episcopal endeavors in Wayne.

Later that summer, sparked by the encouraging increase in attendance, there was a new development for local Episcopal worship. Early in September, Mary McHenry Cox, ever the organizer, arranged for a mailing to fifty-three people within the community with the following invitation:

“You are respectfully invited to attend a meeting of Residents (and Sojourners) of Wayne and its vicinity to be held in Wayne Lyceum Hall on Saturday September 12, 1885, at 5 o’clock PM, to consider the propriety and feasibility of creating an Episcopal Church at Wayne. A site for the proposed church has been promised as a gift.” 13

At this first organizing meeting on September 12 at Lyceum Hall, only eight individuals attended but several names would become familiar to the effort. Besides Mary and John Cox, two other notables included Dr. Joseph C. Egbert, M. D., and R. Evans Peterson. The reader will recall that Dr. Egbert was the Wayne physician asked by Mary Cox to become medical officer serving the Indian School during the summers of 1884 and 1885. And 47-year-old R. Evans Peterson was none other than the eldest son of the publisher who made George W. Childs a full partner in his firm in 1849. With Child’s marriage to Emma Peterson, R. Evans Peterson was thus Childs’ brother-in-law. Peterson had moved to the “new Wayne” in 1881, and was now fast becoming one of the community’s most influential citizens. Mr. Peterson was immediately elected Chairman of this first feasibility meeting, and John Bellangee Cox chosen as Secretary. One of the meeting’s first announcements was that developer George W. Childs had stated his wish, at the right time, to donate a plot of land upon which to build an Episcopal church within Wayne. Though the property’s exact location was not stated, Dr. Egbert quickly moved “that the Chairman appoint a Committee of Four to acquaint Mr. George W. Childs with the proceedings of this meeting.” 14

Two weeks later, on September 29th 1885, the newly-formed “Committee of Four”, accompanied by 28-year-old Wayne draftsman, aspiring architect and newly-appointed vestryman T. Mellon Rogers,15 met with Mr. Childs at his office inn Philadelphia to discuss the investigative progress envisioned for building a new Episcopal church. Before leaving, it is recorded that Mr. Childs was shown several architectural drawings for the proposed Church prepared by Mr. Rogers.

VII.

The Lincoln Institution’s Indian School returned to their main Philadelphia campuses at the end of September 1885, and with that return the weekly Episcopal service at the Lyceum Hall ended. But with the tantalizing chance that Episcopal worship might be sustained in Wayne, a former Wayne postmaster, George W. Brown, offered the use of the parlor in his home at 107 N. Wayne Ave. as a weekly worship space. The Rev. George A. Keller, rector of Old St. David’s Church, agreed to conduct a service every Sunday afternoon at Mr. Brown’s home, and the first service was held on February 21st, 1886. Twenty persons attended. These services in Mr. Brown’s parlor continued for three months until increased attendance required a larger venue. Once again, Mr. Childs offered his help, giving permission to the growing congregation now calling itself “Saint Mary’s Protestant Episcopal Church, Wayne, Pennsylvania,” to use vacant houses awaiting sale or occupancy within the Wayne Estate for weekly worship. In quick succession it is recorded that eight homes were gratefully used, only to be rented or sold soon after services were begun in that location. Just as the parishioners were beginning to feel like nomads, an arrangement was made with the agent of the Wayne Estate to provide the wandering parish the weekly use of the “Library Building” (most likely the Old Wayne Hall on the site of today’s American Legion building at 401 East Lancaster Avenue) until the congregation could build its own sanctuary.16

VIII.

As the 1885 summer session for the Indian School in the former Siterville was drawing to its close, the managers of the Lincoln Institution were perplexed as to where the 1886 summer term would be held. Several offers to purchase the former Spread Eagle Hotel, now well adapted to the needs of the school, had been rejected by Childs & Drexel. It was evident that the children would not return to the Spread Eagle in 1886, and though the old structure had played its important role for the Lincoln Institution, that role had now ended. The Spread Eagle stood abandoned through 1893, and by the time the 1897 Mueller Atlas of Properties on Line of Pennsylvania R.R. from Rosemont to Westchester (Plate 5) was published, the old inn had been razed.

The school needed to act, and on January 5, 1886, under the personal direction of Mrs. Cox, the Lincoln Institution purchased a ten-acre plot of deeply forested and undulating land just north of Mary and John Cox’s summer home “Ivy Croft”. The new property, straddling portions of both Tredyffrin and Upper Merion townships, was located north of Upper Gulph Road near the intersection of Reeseville Road (now called Croton Road) and Radnor (State) Road.

Because the intent of this purchase was the establishment of a permanent and urgently-needed summer home for the Indian Department of the Lincoln Institution, construction began early in March 1886 on a large two-story frame building, 102 feet long and 45 feet wide, along with an attached chapel,. The buildings themselves were located within the Upper Merion, Montgomery County, portion of the property, with the primary entrance from Radnor Street Road. The structure was completed in mid-summer, and by August 3rd the new school building was occupied by some 100 Indian girls who remained until October 31st. 17 The new summer school was named “Ponemah” (often misspelled as Ponema in atlases). 18

IX.

By March, 1886, six months after the summer of hopefulness that had buoyed the small congregation of Wayne Episcopalians who wanted a church of their own, the actions of the Provisional Vestry of “Saint Mary’s Protestant Episcopal Church, Wayne, Pennsylvania” seem to have eroded that enthusiasm. Inexplicably, the six vestrymen had not kept open a line of communication with the congregation’s largest benefactor. Now, for reasons uncertain, these men had convinced themselves that George W. Childs no longer supported the St. Mary’s project. The disillusionment caused by that belief had in turn sown the seeds of a dangerous rift within the young assembly, and yet the Vestry continued to vacillate on what action to take. Finally, sensing crisis, the Vestry requested the formidable Mary McHenry Cox to once again step into the breach to help regain the initiative. From the Provisional Vestry Minutes of March 26, 1886, we read:

“About a week ago [March 15, 1886] Mrs. Cox saw Mr. George W. Childs in his office. He asked her how the proposed Church was getting on. She replied that it was at a stand-still, owing to his own delay about offering a lot and to the scarcely disguised opposition of the Agent of the Wayne Estate. She furthermore told him that, owing to the delay and the uncertainty occasioned thereby, some, if not a very large proportion, of the strongest supporters of the proposed Church, had given up hope of its success and had signified their intention to join Mr. Lemuel Coffin19 in his undertaking to build a church at Devon, Chester County.”

The relationship between these two strong people, Mary Cox and George Childs, was both exceptionally direct yet collegial. Instead of responding with irritation or even anger at this misunderstanding, George Childs seems to react with surprise. He re-states to Mary his offer of the previous September (1885) to immediately transfer the “piece of ground” south of Louella Mansion to the church, and then has his Wayne Estate manager write a note to the secretary of St. Mary’s Vestry (Mary’s husband, John Bellangee Cox) restating that intention. All of this should have been a great support to the vestry.

Two weeks after Mary’s candid meeting with George W. Childs, two procedural motions recorded within the vestry meeting minutes of March 26, 1886 first encourage, and then jolt, the reader. The encouragement comes from the decision to immediately initiate meetings with several key individuals who had, the previous summer (1885) stated their interest in contributing to the St. Mary’s Building Fund, but had thus far not done so. Not surprisingly, the vestry was unanimous in requesting the talented Mrs. Cox to take on this always politically sensitive, and sometimes onerous, job of fundraising, for which she was so skillful. Mary seems to have willingly agreed to add this important task to her workload.

But it is the second motion which jolts and even flabbergasts the reader. Eleven days earlier the vestry had asked Mary Cox to meet with Mr. Childs to “jump start” his continued patronage. She had been completely successful in that effort, with Childs informing her that he was prepared to initiate an immediate pro bono transfer of the 100’ x 300’ property on Lancaster and Louella avenues for the construction of a church for St. Mary’s. But now, instead of expressing gratitude for Childs’ largess, the vestry instead declares that the timing for such a conveyance is not convenient for them:

“ … the Secretary was instructed to reply to Mr. Childs that we are not at present prepared to accept the conveyance of the lot because time is required to ascertain what money can be raised for the Building.” 20

The vestry’s obstinacy seems extraordinary considering the efforts extended to resolve this matter. However, it appears Mr. Childs and Mrs. Cox both kept their good humor towards each other, and both towards the St. Mary’s leadership. 21

X.

Though the congregation continued to grow and become more visible in Wayne over the next two years, a paucity of St. Mary’s Vestry Minutes and other interpretive documents makes it difficult to know the exact size of the parish or how robust was its Building Fund during this period. What we do know is that the vestry had successfully obtained the important consent of the Episcopal Bishop of Pennsylvania, the Rev. Ozi William Whitaker, D. D., to admit the new parish of St. Mary’s in Wayne into the Diocese. The parish’s official name, as stated in its first Charter accepted by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania on December 31, 1887, was recorded as: “The Rector, Church Wardens and Vestrymen of Saint Mary’s Church, Wayne, Radnor Township, Delaware County, Pennsylvania.” With the generous and ongoing support of Drexel & Childs, and of their Wayne Estate, St. Mary’s congregation was allowed continued use of the Wayne Library Building for their weekly worship services well into 1889.

As an aside: an interesting article from October 1886 in the “Among the Architects” section of the esoteric publication Builder and Real Estate Advocate, provides insight into the vestry’s dream of building a home for St. Mary’s: “Messrs. Culver and Rogers … have plans for … a frame church at Wayne, to be used as a chapel for the Episcopal church.” 22 Realistically, however, at that time the parish still had no more than a promise of donated land upon which to build a church home, and there was no further action taken in regards a frame structure.

On the morning of January 3, 1888, John Bellangee Cox, husband of Mary, prominent Philadelphia attorney, Secretary of the Fairmount Park Art Association, Vestry Secretary of St. Mary’s Church, Wayne, and a man “widely known in society circles,” suddenly collapsed while eating breakfast and died of a massive heart attack at age 48. Mrs. Cox’ anguish was profound, but in the ensuing months she seemed able to harness at least a portion of her grief in ways to help others. John and Mary had always cultivated a wide and diverse social circle throughout the Philadelphia area, and now, interested in accelerating the establishment of an Episcopal church in Wayne, creative ideas to help St. Mary’s find a permanent home began to germinate in her mind. Mary had a friend who served as rector of an Episcopal church in Philadelphia. She had become aware that this clergyman, the scion of an extremely wealthy family, had stated his desire to build a memorial church to honor his mother and father, and that he might be willing to donate a significant amount of his own assets to fulfill this dream.

XI.

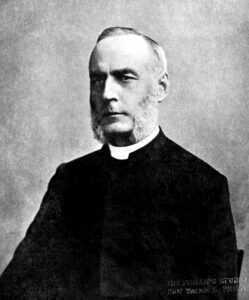

This leads us to the participant directly responsible for the creation of St. Mary’s Memorial Church: the Rev. Dr. Thomas K. Conrad, D. D.

Thomas Kittera Conrad was born in Philadelphia on January 19, 1836, the son of Harry I. and Hannah S. Conrad. After growing up in a life of extreme privilege, he entered the University of Pennsylvania where he received his B.A. degree in 1855, and his master’s degree three years later. Deciding to pursue the career of a cleric, he pursued theological training in Philadelphia and was ordained an Episcopal priest in 1860. He began his career as a parish priest in Philadelphia, and during that time received his doctor of divinity degree from Pennsylvania College, Gettysburg, in 1868. Over two decades he served as rector of four parish churches, two each in Philadelphia and New York City. In 1882, at the age of 46, this confirmed bachelor married Anne Frazer of Philadelphia. Five years later, after taking a foreign sabbatical, Dr. Conrad agreed to return to Philadelphia to become rector of the small Old St. Paul’s (Episcopal) Church in the Society Hill section of Philadelphia at 225 S. Third Street. 23

It was in the fall of 1888, while Dr. Conrad was rector of Old St. Paul’s, that Mary McHenry Cox first discussed with him his possible interest in coming to Wayne to build his Memorial Church. It is clear that Dr. Conrad trusted Mrs. Cox, and that this opportunity was well received on both sides. He stated that he had established “a fund of $20,000 or thereabouts available for the purpose.” [some $600,000 in 2020 dollars24] He stated a stipulation that his willingness to use his funds to build a memorial sanctuary would be contingent on the Wayne congregation being able to raise the money necessary to build an adjacent Parish building. He detailed to Mrs. Cox his belief that “work could be commenced at once and Services could be held in the little Hall [Wayne Library Building] until the Parish buildings were erected & then in the Parish buildings until the Church was erected.” To the obvious question of his current rectorship at Old St. Paul’s, Dr. Conrad told Mary that he believed it possible to remain in charge there while at the same time assuming the additional duties as rector of St. Mary’s … provided that “he could continue having an assistant at both churches.” With genuine excitement, Mary immediately reported the details of this unexpected opportunity to the St. Mary’s Vestry.

The Minutes dated October 24, 1888 cite the Vestry extending:

“… a call to the Rev. Dr. Thos. K. Conrad to act as rector to the Church of St. Mary’s P. E. Church at Wayne in addition to his charge at St. Paul’s P. E. Church in Philadelphia.”

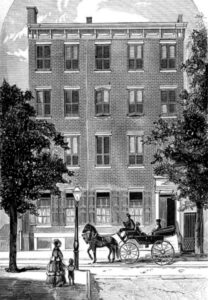

During the following six days, several interviews were conducted, and events progressed favorably. The response from Dr. Conrad concluded the matter:

During the following six days, several interviews were conducted, and events progressed favorably. The response from Dr. Conrad concluded the matter:

1707 Walnut st. Philadelphia

Oct 30th 1888

Mr. R. Evans Peterson, Chairman of Committee

My Dear Sir,

Will you kindly convey to the vestry of St. Mary’s Church, Wayne, my acceptance of their invitation to become the rector of the Parish. It is understood that I am still to retain my Rectorship of St. Paul’s Church, Phila., an arrangement to which both the Bishop of the Diocese and the vestry of St. Paul’s have given their formal assent. A part of my duty at Wayne will of course be delegated to an assistant. With the earnest prayer that our relations may be for the glory of God and the edification of His Church.

I am,

Yours very sincerely,

Thos. K Conrad 25

XII.

January of 1889 was to be a nail-biting, “hang onto your hat” month for the Episcopal congregation in Wayne. The St. Mary’s Building Committee, officially organized on January 14th, 1889 with the new rector, Dr. Thomas Conrad, as Chairman, set as its first goal to:

“… secure [architectural] plans for the construction of a church to seat 300 persons, and not cost over Twenty five Thousand dollars; and a parish building to contain Sunday School and Infant School rooms and such other offices as are necessary in such a building, at a cost not to exceed Seven Thousand dollars.” 26

The Committee immediately sent invitations for a design competition to the distinguished Philadelphia church architect Charles Marquedent Burns, and to the creative Philadelphia architectural firm of Constable Bros. & Rogers, comprising Stevenson and Howard Constable and Thomas Mellon Rogers (who continued to serve as one of St. Mary’s original vestrymen). But the designs furnished by the two firms each exceeded the clearly stated financial constraints, and were thus both rejected. Dr. Conrad then personally sought consultation from the acclaimed Philadelphia architect George Watson Hewitt, whose specialty was ecclesiastical design. Mr. Hewitt carefully reviewed St. Mary’s specifications, and firmly declared that, based upon his long experience, such a set of buildings could not be erected for the amount budgeted.

Remaining confident despite this disconcerting advice, the Building Committee now invited for interview the prolific and diversified Philadelphia architectural firm of Wilson Brothers and Co. (Joseph and John Wilson, and Frederick Thorn). The Committee was shown an array of church designs from Wilson Brothers’ bulging portfolio. One of those plans, created in the style of a simple “English Village Church,” was not only found aesthetically pleasing, but could be built within the stated cost parameters. The enthusiastic Committee immediately requested preliminary sketches and estimates, which were quickly forthcoming.

Almost three years had passed since George W. Childs had originally declared his readiness “to transfer to your Church the piece of ground opposite Louella Mansion” … and then only to be rebuffed by the vestry. But now, on January 23rd of 1889, Deed #13276 offered an agreement with the vestry whereby Anthony J. Drexel, and his “Attorney in Fact” George W. Childs, offer, “in consideration of one dollar,” to turn over to St. Mary’s a property “containing one acre and five hundred and seventy four thousandths of an acre more or less” on the southeast corner of Lancaster and Louella avenues. The explicit condition of that gift was that “a Protestant Episcopal Church shall be erected upon the lot …within three years from the date hereof and that in the event of said church not being erected within said period the said lot of ground shall revert to the said Anthony J. Drexel and George W. Childs …” The document was gratefully consummated.

Then, at almost the exact happy moment that both property ownership was assured and Wilson Brothers & Co. had saved the day with their plan, a bombshell was delivered to St. Mary’s leadership. Mr. Frank Smith, manager of Childs & Drexel’s Wayne Estate, asked for an urgent meeting with Dr. Conrad and the Building Committee, to inform them that Mr. Drexel would soon be opening his “Drexel Industrial College for Women” 27 at the former Louella mansion in Wayne, directly across Lancaster Avenue from the proposed St. Mary’s church. Mr. Drexel wished to offer a donation to the parish in the amount of $5,000 [approximately $150,000 in 2020 dollars] … provided that architectural changes be immediately made to the already agreed upon Wilson Brothers church design so as to provide additional seating for the two hundred resident students who would attend Drexel’s new college. The Committee was dumbfounded, and urgently discussed the pros and cons of undertaking such a significant and costly addition to the sanctuary. But realizing that rejection of Drexel’s offer would quite possibly have negative consequences to St. Mary’s, the vestry accepted Drexel’s largess and condition, and Wilson Bros. was immediately notified of the need for architectural adjustments.

In an extraordinary effort, just days later (January 29, 1889), Wilson Brothers and Company submitted adapted ground plans and an initial perspective drawing of both the proposed Parish building which was to be completed first; and the church, including the Drexel-driven adaptation in which transepts would widen the center of the sanctuary so to accommodate the two hundred Industrial College girls. The architects affirmed that they had received preliminary bids that came within the revised budget as cited by the Committee (and now increased by the Drexel gift). On February 2nd Wilson Bros. was notified of the acceptance of their plans, and that they had been chosen as the project architects by the Vestry. The firm then proceeded with detailed drawings for the adjacent Parish building, and set about creating additional perspective drawings of the much larger church interior to enable Dr. Conrad and the Committee to better judge its proportions.28

There was another important obstacle to be overcome –the congregation’s promise to complete its fund-raising so as to pay for the Parish building and the grading of the lot. The agreement originally made to Dr. Conrad by the Vestry was that St. Mary’s would raise up to $10,000 to build the Parish building – and Dr. Conrad would build the church with his own funds. The Parish building as now designed and approved would cost less than $8,000, and yet the congregation had raised nothing like that amount. It was projected that the Parish building would be completed by the fall of 1889, and then serve as a temporary worship space pending the opening of the church in the following spring of 1990. It was a matter of good faith to raise the remaining balance quickly so that by the following spring the church could be consecrated – which in the Episcopal denomination could not be done so long as there was debt on the property.

Beginning in mid-February, the Vestry first led a concerted effort among all St. Mary’s parishioners to raise the remaining funds required to build the Parish building, pay for its fitting out, and allow for the necessary grading of the lot. Several generous contributions came from that effort, but by the beginning of May the momentum of this fund-raiser within the parish had exhausted itself. So the vestry elected to undertake a very bold move whereby every resident within Wayne was to be canvassed, and a request made to consider some donation to St. Mary’s Building Fund to erect a “parish house.” The result was both extraordinary and surprisingly generous – it was recorded that a pledge was either received or promised from “nearly everyone” who was called upon. It was warmly remembered that “the interest taken, and the kind reception, was universal, not only amongst those of our own faith, but of all denominations.” 29

Fundraising efforts continued through the summer, and it is even recorded that three members of the Vestry called upon their longtime benefactor George W. Childs to close the gap towards the remaining sum still required for the Parish building. As usual, they were not disappointed. A citation from the February 1890 Vestry Minutes notes that: ” … the Secretary was requested to express to Mr. George W. Childs the thanks of the Vestry for his liberal donation to the Building Fund of the Parish House.”

XIII.

When architects Wilson Bros. & Co. initially confirmed their estimate to build an “English Village Church” for $25,000, Dr. Conrad and the Building Committee were pleased not only with its unpretentious design but also with the inclusion of many stunning details. But now, with the vestry’s acceptance of Anthony Drexel’s gift and condition, much would have to be adapted. The cost of constructing the sanctuary with the additional transepts was considerably in excess of the $5,000 received from Drexel. Thus, to keep the project from foundering, the architects were obliged to propose many less-expensive substitutions in order to remain within the parish budget.

Requests for quotations were distributed, and bids received, for the erection of the church and Parish building. It was decided that Wayne general contractor John C. Kelly was both the lowest, and the best, bidder, and on May 6, 1889 the contract with Mr. Kelly was awarded, with work to commence immediately.

But even before the construction process began, Dr. Conrad was growing increasingly dismayed. On May 3, 1889, the Building Committee reported to the Vestry that:

“… the Rev. Dr. Conrad has informed (the Committee) that, upon further consideration, he has concluded that the proposed modifications to the Church plans would destroy so much of the beauty of the structure.”

Dr. Conrad, realizing that his dream of the “perfect” Memorial church now risked tarnish because of the necessary cost-cutting substitutions, now began reinstating upgrades for which he would have to pay over and above his stated commitment. On June 24th, Dr. Conrad informed the Building Committee that he would erect stone arches for the church and the Baptistry. And two weeks later, on July 8th, he again ordered upgrades for tiling the chancel, baptistry, aisles and the vestibules.

The church and its mandated accoutrements (excluding the Parish Building) would ultimately cost over $38,000 (approaching $1,500,000 in 2020 dollars). Less Mr. Drexel’s contribution, this represented a total largess by Dr. Conrad some 65% more than he originally discussed with Mary McHenry Cox in the fall of 1888.

The sanctuary’s cornerstone was laid amid great rejoicing and with impressive ceremony at 5:30 p.m. on Thursday, June 27, 1889. Over 2,000 people attended as the church was dedicated “to the glory of the Eternal Trinity and in loving memory of Harry Conrad and of his wife, Hannah S. Conrad.” The Bishop of the Diocese of Pennsylvania, O. W. Whitaker, presided.

Of that cornerstone- laying ceremony, a Vestry Minute dated October 1, 1889 describes the event:

“Arrangements were made by the Committee for the transportation of visiting clergy and the choristers, which through the courtesy of the Officers of the Pennsylvania Railroad were gratuitous. Dr. Conrad entertained the Clergy, and the Choristers were entertained by the ladies at the Merryvale Grounds [Merryvale Cricket Club, later called the Radnor Cricket Club]. The corner stone ceremonies were of such a character that to those who were present any comment is unnecessary. They will never be forgotten.” 30

Then, at a period when changes were continuous, yet another unforeseen alteration was announced. In mid-August, 1889, Dr. Conrad was surprised by the news that the Drexel Industrial School for Girls would not be located in Wayne.31 The construction was already well-advanced, and the church’s foundation, including that to support the transepts, was already in place. Though Mr. Drexel was not seeking any refund of his gift, the rationale for constructing the now-unnecessary transepts must have been galling. To offset expenses, it was decided to cancel the purchase and installation of the pews within the transepts, and to simply tile the floor space on which the pews would have rested.

XIV.

Exacting 1890’s descriptions of the church and parish building, as they neared completion, are provided from two sources: the profusely illustrated promotional booklets published by the Wayne Estate, c. 1892 32; and the wonderfully descriptive book Rural Pennsylvania in the Vicinity of Philadelphia, written by the Rev. S. F. Hotchkin in 1897.33

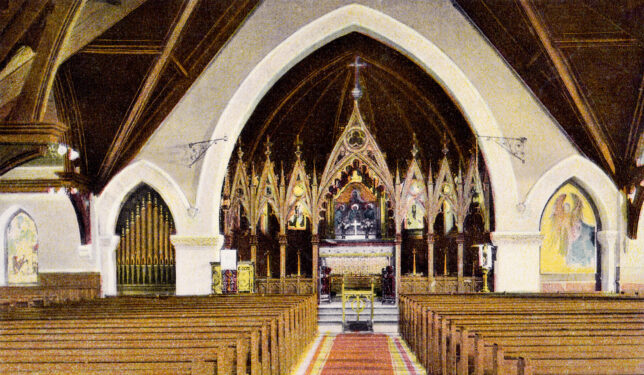

The church and parish house were built of distinctive gray limestone from the quarries of Avondale, southern Chester County, with cut work of Indiana limestone. The architectural style is Norman-Gothic, or alternatively called “English Village Church.”

The church is of a cruciform geometry, with a total length of 113 feet, and its width across the transept is 82 feet. The nave occupies the entire length of the building, with the roof supported by heavy Gothic braces. The massive tower at the corner of the north transept rises some 80 feet, and contains a chime of ten bells varying in weight from 230 to 2100 pounds. The base of the Tower forms a Baptistry floored with mosaic. The chancel has a depth of 33 feet, and with its altar faces east.

The parish building is 56 by 54 feet, and connects with the church by a cloister and porte-cochere. It is furnished for Sunday and Infant School rooms, class rooms for guild work, a library and a kitchen.

XV.

In a report to the Vestry dated February 17, 1890, Rector’s Warden R. Evans Peterson spoke briefly that during the previous summer Dr. Conrad had directly contracted with America’s best-known pipe organ design and manufacturing company, Hook and Hastings of Boston, to have them create a very special organ for the Memorial church. The organ, selected and paid for by Dr. Conrad, contained eight hundred and thirty nine pipes, and twenty four stops. This instrument was transported to Wayne and erected over several days during the fall of 1889 by Hook and Hastings technicians.

It was also reported that Dr. Conrad had personally contracted with the well-known ecclesiastical stained glass designer and manufacturer J&R Lamb Studios of New York City to emplace the stained glass windows and their memorials, and to assist in the decoration of the church. Obviously, only the best was sufficient for Dr. Conrad and his church.

In mid-October, 1889, general contractor John C. Kelly completed his work on the Parish building on schedule. The congregation of St. Mary’s would at long last be able to leave the Wayne Library Building where they had met weekly over the last three years for their corporate worship, all this thanks to the generous and continual support by George W. Childs and the Wayne Estate.

From a letter written by Dr. Conrad to Mr. Peterson just after the opening of the Parish House on October 20, 1889:

“… the carpets were down, the steam boiler was kindled, the chairs were in place, and nearly all arrangements were made. Even with our nine dozen chairs, there were not enough to fill the room and I borrowed forty or fifty more from Miss Boughter [of Louella Mansion]. Mrs. Hare and the other ladies had provided a profusion of beautiful flowers, some from the woods and some loaned by Adelberger. On Sunday, in spite of weather predictions, the day was bright and pleasant, and everything seemed to combine to make the service beautiful. … The 10.45 service was, of course, the great occasion of the day. Every place was filled, the music was admirable, the service hearty, and from the general congratulations that I received, I think the occasion was, in its way, as much a success as the laying of the cornerstone was.” 34

All through the winter months and early spring of 1889-90, the workers and sub-contractors of John C. Kelly, together with the decorative artisans from J&R Lamb Studios of New York City, worked unceasingly towards the goal of making the Church ready for occupancy by not later than the 1st of April, 1890. They succeeded in meeting that goal, and it was with great rejoicing that Dr. Conrad and his growing flock of Wayne Episcopalians celebrated their first worship service in their new St. Mary’s sanctuary, with its consecration on Easter Sunday, April 6, 1890.

An excerpt from an article in the Philadelphia Times sums up the spirit of the event, and the significance and gratitude for what had been accomplished:

“Easter day brought something beyond its usual pleasures to the Episcopal worshippers of Wayne in the occupancy yesterday morning [April 6, 1890] of the splendid new St. Mary’s Church, which, through the munificent liberality of Rev. Thomas K. Conrad, D. D. … is practically a gift to the denomination.” 35

POSTSCRIPT

Over 120 years have elapsed since St. Mary’s Memorial Church was opened for public worship, and today the parish continues to serve the religious and social needs of the people of Wayne and its environs. Yet I daresay few parishioners, let alone the general public, are aware of the narrative presented. A place can become undervalued and taken for granted unless its history is made fresh and available.

As this author completed his research, his curiosity was still fully engaged, still seeking answers with questions beginning: What happened to … ? Perhaps the reader has the same curiosity?

THE PEOPLE

The Rev. Dr. Thomas K. Conrad, D. D.

The Rev. Thomas Kittera Conrad, D.D., whose dream was to build a church to honor his parents, only lived to enjoy his church and its people for three years after its consecration. In the spring of 1893, Fr. Conrad had complained of pains in his heart which, though not considered serious, prompted his doctor to recommend rest in the nearby rectory. During that confinement he caught a severe cold which developed into pneumonia and, at age 57, ended fatally. Thus, this good and generous man, rector of numerous Episcopal churches including St. Mary’s, and who in his last years also served on the board of the newly created Drexel Institute, died in Wayne, Pennsylvania on May 28, 1893. He was a man of considerable wealth whose estate, obtained through inheritance, was reported in an obituary to be $2,000,000 (some $60,000,000 in 2020 dollars) at his death. He and his wife Anne Frazer Conrad (1839-1914) had no children, and they lie together at rest in Laurel Hill Cemetery, Philadelphia.

George W. Childs:

George W. Childs, the boy that believed that a man could be both “liberal and successful,” achieved both dreams. But though a brilliant businessman, it was for his generosity that Childs left his greatest legacy. From his New York Times obituary one learns of his big-heartedness of spirit … not an attribute often used to describe the truly wealthy:

“The world will always remember George W. Childs best as the open-handed, kind-hearted philanthropist. His business success was tremendous. From a poor, obscure boy he worked himself up until he was ranked among the great millionaires of the country … His unusual attainments and striking personality made him one of the conspicuous public men of the country (yet) the great and shining beauty of his liberality to others lay in the fact that it was so unostentatious.” 36

Mr. Childs died on February 3, 1894 at age 65 from the effects of a stroke suffered two weeks earlier. But those closest to him believed his death at least in part attributable to a broken heart over the death of his lifelong best friend, Anthony J. Drexel, just seven months earlier. Drexel had died on June 30, 1893 of a heart attack at the age of 66. It was recorded that “for a quarter of a century they lunched with each other each noon.” 37 Childs was survived by his widow, Emma Bouvier Peterson Childs (1842-1928). They had no children. At the time of his death, Childs’ fortune was reported in his obituary at $5,000,000 (some $175,000,000 in 2020 dollars), and yet it is estimated that he gave away half of everything he earned.

He and Emma lie at rest in Laurel Hill Cemetery, Philadelphia.

Mary McHenry Cox

Mary McHenry Cox, a leader in the religious, philanthropic and social life of Philadelphia for decades, died at her summer home in Wayne at age 79 on November 3, 1906 after a long illness. Mrs. Cox was long known as “The Orphans’ Friend,” and it was reported that the children of her Lincoln Institution attended her funeral.

“The Indian girls at the Lincoln Institution continued to return to Ponemah each summer up into the first decade of this century. When subsidies for the Indian children were discontinued by the government, the program was supported largely through the donations and contributions of Mrs. Cox. In addition to the original large frame building, several smaller structures were added to the school’s summer facilities, and in 1890 and 1903 a total of ten more acres in Tredyffrin was added to the site.”

“After the Indian Department was discontinued in the early 1900s, the primary efforts of the Lincoln Institution were directed to homeless orphan boys between the ages of five and fourteen and coming from poor environments. In October of 1915 the Lincoln Institution was merged with the Educational Home organization, and in November of 1922 they were both merged with the Big Brothers Association. The property in Tredyffrin was sold on June 22, 1924.” 38

Mary McHenry Cox and her beloved husband John Bellangee Cox lie at rest in Laurel Hill Cemetery, Philadelphia.

R. Evans Peterson

Robert Evans Peterson died of a cerebral hemorrhage at age 72 on February 16, 1910. He had been a prominent figure within several publishing firms in Philadelphia, including the Childs & Peterson Publishing Company started by his father. He was a brother of Emma Bouvier Peterson Childs (Mrs. George W. Childs). Moving to Wayne in 1881, he soon became one of its prominent citizens. He was one of the original vestrymen at St. Mary’s Church, and chosen by Dr. Thomas K. Conrad as his first Rector’s Warden at St. Mary’s. Even after relocating from Wayne to Pasadena CA in 1902 to be close to one of his daughters, he had been requested by St. Mary’s to remain a member of its vestry. His body was brought back to Philadelphia and is interred at Laurel Hill Cemetery. 39

Joseph C. Egbert, M.D.

Almost exactly one year after the consecration of the new St. Mary’s Church, its first wedding ceremony was celebrated on April 22, 1891 in which Katherine Miller of Philadelphia was joined with 35-year-old Dr. Joseph C. Egbert, M.D. of Wayne. It will be remembered that Dr. Egbert was the up-and-coming Wayne physician whom Mary McHenry Cox asked to be the consulting physician for the Lincoln Institution during its earliest summer sessions at the Spread Eagle in 1884-5. The Rev. Dr. Conrad officiated in the high church ceremony, and it was reported that, in addition to many prominent guests, a number of Indian girls from the Lincoln Institution came out from Philadelphia to join the large audience. 40

On January 17, 1923, Dr. Egbert, aged 67, died at his Wayne home of “acute indigestion.” At the time of his death he was a widely-regarded Main Line physician, and also served the Pennsylvania Railroad as its physician for its Main Line section. He had served St. Mary’s Episcopal Church as one of its original vestrymen, and at his death he still served as its Accounting Warden. His widow Katherine survived him. 41

The First St. Mary’s Rectory

In October 1888, when the St. Mary’s Vestry was inviting Dr. Conrad to become its first rector, Thomas and Anne Conrad resided in an elegant three-story row home in Center City Philadelphia at 1707 Walnut Street, one-half block east of Rittenhouse Square. The Conrad’s were always known as gracious hosts, and after Dr. Conrad became rector of St. Mary’s the first few Vestry meetings were held at the Conrad’s Philadelphia home. The last of these meetings, cited in the Vestry Minutes “at the house of the Rector, 1707 Walnut st.,” took place on January 29, 1889.

Soon thereafter, while retaining ownership of their Philadelphia home, Dr. and Mrs. Conrad temporarily acquired a home in Wayne, and on May 8, 1889 the Minutes record: “A special meeting of the Vestry was held this day at the residence of the Rector on Wayne avenue.” But the Conrad’s wished to personally build a large rectory with their personal assets, on property immediately east of the land donated less than three months earlier by Drexel & Childs where the church would rise – a plot 200’ wide and 300’ deep referred to on an 1882 Wayne property map as “Lot 125.” On April 8, 1889, Deed #13625 records the transfer of this property from Anthony J. Drexel and his wife Ellen, and George W. Childs and his wife Emma; to “Anne Frazer Conrad, Wife of the Reverend Thomas K. Conrad, D. D. of the City of Philadelphia,” for the sum of $4,000.

The Conrad’s had already independently commissioned Wilson Brothers, the same architectural firm which had designed the church and parish building, to create the plans for a palatial rectory that would become one of Wayne’s grand houses, to be built concurrent with the construction of both the church and the parish building. The first official reference to the completed rectory at St. Mary’s is dated April 8, 1890, two days after the church’s consecration. in the Vestry Minutes.

Eight years after the Memorial church and the rectory had been completed, and five years since Dr. Conrad had passed, a special vestry meeting was convened on August 3, 1898 to consider a proposition. An attorney representing Mrs. Anne Frazer Conrad now stated that Mrs. Conrad, who had continued to live in the rectory since her husband’s death, now wished St. Mary’s to consider buying the residence as a permanent rectory for the parish. He was instructed “to offer to the vestry the house now owned and occupied by her adjoining the church on the east … for the price of $10,000.” After much deliberation, the Vestry agreed, in a unanimous vote, to purchase the Conrad residence. Soon thereafter, Anne Conrad returned to her home in Philadelphia and became active in philanthropy at The Church of St. Luke & the Epiphany (Episcopal) at 13th and Spruce streets.

It was recorded years later: “Perhaps there were many reasons against the purchase of this property, chief of which was the large size of the house; but the necessity of the parish controlling the property so near to the church, which might have come into the hands of most undesirable occupants, overweighed every consideration against it.” The Conrad rectory served the residential needs of three of St. Mary’s subsequent rectors and their families until it was sold to Radnor Township on November 20, 1929 for use as its Administration Building. So it remained in service until the structure was demolished in the 1960s after the Township moved its operations to its new site on Iven Avenue. Today that property, at 212 E. Lancaster Ave., was most recently occupied by the TD Bank building.

The Memorial Name for St. Mary’s … and its Removal:

The name of a place is important. And for the historian, any change of that name is generally worth pursuit.

On April 14, 1890, just days after the long-awaited consecration of the exquisite new Church, the Reverend Thomas K. Conrad and his wife Anne Frazer Conrad presented the vestry a Deed of Gift for their consideration and approval. This Deed recites that the Conrad’s wish to transfer to “The Rector, Church Wardens and Vestrymen of Saint Mary’s Church, Wayne, Radnor Township, Delaware County, Pennsylvania” all rights of ownership in the Church Building “which he had caused to be built at his own expense, a cost largely in excess of the said sum of Twenty five thousand ($25,000) Dollars.”

There were, however, four conditions attached to this Deed of Gift, the second of which directly focused on the perpetuity of intention: “It is understood that the said Church Building known as Saint Mary’s Church Wayne was erected to be forever a Memorial of Harry Conrad and of Hannah S his wife, the father and mother of the said Thomas K. Conrad, D. D.” The Vestry acknowledged the extraordinary largess given so willingly by the Conrad’s without which this feat of construction could never have been accomplished. Unanimously and thankfully, the vestrymen accepted the Conrad’s Deed of Gift, with each of its stated conditions, and document #1578 was entered by the Delaware County Recorder of Deeds on August 15, 1890.

No hasty action was taken regarding a formal name change stemming from the Deed of Gift. But three years after Dr. Conrad’s death, under the rectorship of The Rev. John R. Moses, an application for an amendment to the parish Charter was filed on May 2, 1896 before the Court of Common Pleas of Delaware County PA on behalf of “the Rector, Church Wardens and Vestrymen of St. Mary’s Church Wayne” Specifically to be added was “the word ‘MEMORIAL’ in the name and title … immediately after the name ‘St. Mary’s’, so that the name and title of said Corporation shall thereafter be ‘The Rector, Church Wardens and Vestrymen of St. Mary’s Memorial Church, Wayne, Radnor Township, Delaware County, Pennsylvania’.” This amendment application was approved and filed with the Delaware County Recorder of Deeds on June 10, 1896.

That Corporate moniker would remain official for some seventy-five years, along with its more commonly used variant “St. Mary’s Memorial Church, Wayne, PA.” But in the 1960’s (November 1964, under the rectorship of The Rev. William L. Kier), a vestry-initiated amendment to the Charter of St. Mary’s proposed the explicit elimination of the word Memorial within its name. Just over a year later, on January 19, 1966, the official Corporation name was successfully re-registered with the Secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of State as “Saint Mary’s Episcopal Church, Wayne, Radnor Township, PA”– the official parish name to this date.

It takes much time and effort, and some expense, to modify a corporate Charter and its legal designation, and it is not done lightly. So why did St. Mary’s rector and vestry chose this moment to remove the well-earned Memorial from the formal name. Was it just the “Sixties” … a time to shake things up ? Nowhere in any Parish, Diocesan or Commonwealth document, or even within St. Mary’s official History published in 1987, can I find a single stated reason, general purpose, mere opinion or even simple reference for this 1960’s excision. What prompted the parish to turn its back on its Memorial promise to remember the Conrad’s … and the gift of such extraordinary generosity for which we are all beneficiaries to this day? I wish I knew.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to express my particular gratitude to four individuals who made this journey of exploration more productive:

- Fr. Joseph Smith, rector of St. Mary’s Church, Wayne, who made available invaluable handwritten copies of the original parish documents from the 19th century – without which I could not have proceeded on this project with any certitude.

- Michael Krasulski, Archivist for the Episcopal Diocese of Pennsylvania, who helped me penetrate the lineage of Diocesan parishes, and its publications from a century ago.

- Meg Weiderseim, researcher extraordinaire, who helped me immeasurably in precisely tracking down 19th century news clippings.

- Finally, to Greg Prichard, who asked me to write this narrative about my parish church of which I then knew so little … and who provided invaluable assets about St. Mary’s Church from the archives of the Radnor Historical Society and from his own collection.

Roger D. Thorne is a parishioner at St. Mary’s – Wayne, and a past president of the Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society in Chester County,

FOOTNOTES

1. Bob Goshorn, ” The Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike Road Company,” Tredyffrin Easttown History Quarterly, Berwyn, Pennsylvania, Volume 23, Number 1, Pages 25-36 – January 1985.

2. Herb Fry, “The Village of Spread Eagle,” Tredyffrin Easttown History Quarterly, Berwyn, Pennsylvania, Volume 36, Number 3, Pages 77-90 – July 1998.

3. David W. Messer, Triumph II: Philadelphia to Harrisburg, 1828-1998; 1999, p. 13.

4. “A Splendid Driving Road,” West Chester, PA: Daily Local News, May 18, 1881.

5. “Indian Girl Pupils,” Philadelphia Times, April 13, 1884.

6. Julius Sachse, The Wayside Inns on the Lancaster Turnpike between Philadelphia and Lancaster. Lancaster, PA, 1915, p. 41.

7. Bob Goshorn, “Ponemah, Land of the Hereafter,” Tredyffrin Easttown History Quarterly, Berwyn, Pennsylvania, Volume 25, Number 1, pp. 20-26 – January 1987.

8. Rev. Charles Maurice Armstrong, “Sermon in Commemoration of the Twenty-first Anniversary of the laying of the corner stone.” (St. Mary’s Memorial Church, Wayne, Pennsylvania, June 26, 1910).

9. https://archive.org/details/georgewchildsab00partgoog/page/n7/mode/2up

10. Sachse, p. 41.

11. “Indian Girl Pupils,” Op. cit.

12. Goshorn, “Ponemah” p. 111.

13. Vestry Minutes, St. Mary’s Episcopal Church, Wayne Pennsylvania, September 12, 1885.

14. Vestry Minutes, St. Mary’s Episcopal Church, Wayne Pennsylvania, September 29, 1885.

15. Philadelphia Architects and Buildings database. Biography of Thomas Mellon Rogers. Philadelphia, PA: The Athenaeum, 2020. https://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/ar_display.cfm/26906

16. Armstrong, “Sermon in Commemoration …”

17. Goshorn, “Ponemah” p. 112

18. The word Ponemah is derived from the Ojibwe word baanimaa, meaning “later (on), after(wards)” (https://ojibwe.lib.umn.edu/), and is found at the end of the portion entitled “The Death of Minnehaha” from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1855 poem The Song of Hiawatha: “… Soon my task will be completed, Soon your footsteps I shall follow To the Islands of the Blessed, To the Kingdom of Ponemah, To the Land of the Hereafter!”

19. In August 1881, Philadelphia dry goods merchants Lemuel C. Coffin and Joseph B. Altemus purchased several farms totaling more than 300 acres south of the Lancaster Turnpike and west of Valley Forge Road in Easttown Township, Chester County. Their intention was to build a town of “large and handsome country residences,” as well as a luxurious hotel similar to that built by the Pennsylvania Railroad in Bryn Mawr. By August 1882 the Inn at Devon had its gala opening. When that first Inn was destroyed by fire the following year, it was immediately replaced with an even larger and grander hotel … and Devon had become a desirable destination and even a competitor to Wayne. Lemuel Coffin dreamed of creating an impressive Episcopal sanctuary in his new community of Devon, which he intended to call the Church of All Saints, in memory of his departed wife. His dream of such a church, however, would never be realized.

20. Vestry Minutes, St. Mary’s Episcopal Church, Wayne Pennsylvania, March 26, 1886.

21. The author believes there was another “game” being played between the vestry and Childs & Drexel – an attempt to secure for St. Mary’s an even more desirable property in Wayne on which to build their church. On September 29, 1885, the “Committee of Four” from St. Mary’s had met with Mr. Childs at his office and “showed him a paper signed by many residents of Wayne citing their preference, as the site for the proposed Church, ‘the two lots at the South West corner of Wayne avenue and Lancaster avenue’.” But three weeks later, on October 21, 1885, the Provisional Vestry stated that: “… it was Resolved that the offer of Mr. George W. Childs to give a lot for the Church to contain 100 feet in front of the south side of Lancaster avenue and 300 feet in depth along the east side of Louella avenue is accepted with thanks.” Then three years later, in the Vestry Minutes of October 24, 1888, “the Chairman thought it quite probable that the triangle formed by Lancaster and Wayne Avenues, now vacant, could be obtained for the Church lot in place of that opposite Louella Mansion.” St. Mary’s would never occupy the property at Lancaster and Wayne avenues, and would break ground for their new buildings later the following year on the property originally committed by George W. Childs on Lancaster Avenue opposite Louella Mansion.

22. Builder and Real Estate Advocate, October 1886, p. 8.

23. Norris Stanley Barratt. Outline of the history of old St. Paul’s church, 1760- 1898, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. 1917. pp 177-78.

24. Measuring Worth https://www.measuringworth.com/dollarvaluetoday/?amount=25000&from=1888

25. Vestry Minutes, St. Mary’s Episcopal Church, Wayne Pennsylvania, November 3, 1888.

26. St. Mary’s Building Committee Minutes, February 17, 1890.

27. An article from March 1888 in Childs’ Public Ledger had revealed the first evidence that Anthony J. Drexel intended to create this very unusual women’s industrial college somewhere in the Philadelphia suburbs. The article explained that Drexel’s institution, unlike a more classical college education, would train women “in such ways as to help them to employments and occupations in which they could earn a liberal living.” Drexel anticipated that 200 students would board at his school, with an additional 400 to 500 commuting from their homes. The exact location of Drexel’s college was not revealed. Alissa Falcone, The Drexel Institute That Almost Was, Drexel University, August 5, 2016, https://drexel.edu/now/archive/2016/August/Drexel-Institute-That-Almost-Was/

28. Ibid.

29. Ibid.

30. Ibid.

31. After further researching what made similar women’s industrial institutes successful, Anthony Drexel belatedly realized that urban schools were more effective for vocational training. The isolated suburb of Wayne was simply too far distant from Philadelphia for the 400-500 commuter students for which Drexel had planned. By late 1889 Mr. Drexel had a new idea for a nonsectarian and coeducational vocational school, the first of its kind in Philadelphia. That year, construction began on the Main Building of what, by 1891, would be called Drexel Institute of Art, Science and Industry, located on 32nd and Chestnut streets located next to two railroad lines and several trolley lines. This would become the Drexel Institute of Technology in 1936.

32. Emma C. Patterson, Wayne Estate era Churches – Presbyterian, St. Mary’s Memorial Church, Radnor Historical Society, October 14, 1949, https://radnorhistory.org/archive/articles/ytmt/?tag=st-marys-church

33. Rev. Samuel Fitch Hotchkin. Rural Pennsylvania in the Vicinity of Philadelphia. George W. Jacob & Co, Philadelphia, 1897, pp. 254-258.

34. Rev. Charles Maurice Armstrong, “Sermon in Commemoration …”

35. “Occupying a New Edifice,” Philadelphia Times, April 7, 1890.

36. “Death of George W. Childs: The Philadelphia Philanthropist is at rest,” New York Times, February 3, 1894.

37. “George W. Childs Dead,” Gazette, Warrenton, N.C., February 16, 1894.

38. Bob Goshorn, “Ponemah, Land of the Hereafter,” p. 113.

39. “Robert Evans Peterson,” Suburban & Wayne Times, February 25, 1910.

40. “April Wedding Bells,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 23, 1891.

41. “Dr. Joseph C. Egbert,” Philadelphia Inquirer, January 23, 1923.

42. “Mrs. Anne Frazer Conrad,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 20, 1914.

43. Armstrong, “Sermon in Commemoration …”