Stone Being Rededicated at Rosemont Commemorates March to Valley Forge

By EMMA C. PATTERSON

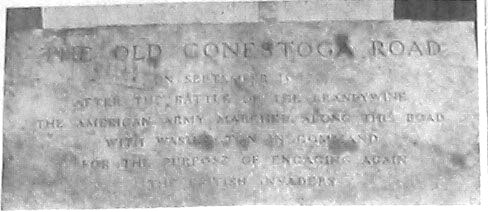

THE OLD CONESTOGA ROAD

On September 15, 1777, After The Battle Of The Brandywine, The American Army Marched Along This Road With Washington In Command For The Purpose Of Engaging Again The British Invader.

On Tuesday, July 4, with ceremony befitting the occasion, a great stone bearing this inscription will be erected in front of the Rosemont School on Conestoga road. It is not a new stone, but one that dates back some seventy years, when in about 1880 the John Converse family had it erected on their property near what is not the overpass of the Philadelphia and Western Railroad, where its tracks cross Conestoga road.

From 1880 until 1906 this stone, measuring some five feet by two feet, with a thickness of about four inches, stood on the Converse property, wehre many a traveller read it in passing. This period of time spans the era of the horse-drawn vehicle to that of the early automobile.

Then in 1906, the Philadelphia and Western Railroad surveyed that part of Radnor township in order to plan for the high speed trains which they hoped to put into operation. This was generally considered as part of a project to have another railroad system into Philadelphia in addition to that of the Pennsylvania Railroad.

This survey showed that the tracks would cross the Converse meadows near the site of the present overpass. This property was therefore condemned and a large fill was made in order to provide for the overpass. The edge of this fill just about covered the old marker, and as time went on it was wholly submerged. It was not until the early part of this year that a crew of Radnor township highway workmen, in cleaning out the culvert, brought it to light again. Their surprise on reading the inscription can well be imagined!

Once discovered, the stone was removed with some difficulty to the township garage from its earthy hiding place. This was done after permission had been obtained from the Philadelphia and Western Railroad, since this culvert is now part of their holdings. The picture which illustrates this column has been made especially for The Suburban by officer Russell Fleming, of the Radnor Police Force.

After due consultation with the Converse family, a choice of a permanent site has now been made from a number of possible ones. This will be just outside the hedge in front of the Rosemont Public School. The ceremony which will accompany it will be part of the Rosemont Civic Association’s Fourth of July celebration. It will be witnessed by not only representatives of that association, of which Frank Fleck is president, but by Radnor township officials and by representatives of the Radnor Historical Society.

The disastrous Battle of the Brandywine was fought on September 11, 1771, on the borders of the stream of that name in a section about ten miles northwest of Wilmington, Delaware, and a few miles inside the Pennsylvania border. Sir William Howe, British Commander-in=chief, had formed the plan of capturing Philadelphia form the south side by a movement by sea to the head of Delaware Bay. Washington got wind of his plans and moved his troops to a strongly entrenched position at the fords over the Brandywine, twenty-five miles southwest of Philadelphia. Here, on September 11, the British attacked Washington and his troops.

In spite of desperate resistance Washington was in full retreat towards Chester by nightfall. The British, however, were too exhausted to persue. Their loss in killed, wounded and prisoners was about 600, as compared to the American loss of 1000. According to “The History of Delaware County,” as written by Henry Graham Ashmead, it was on the day of December 11, 1777, that the Army under Washington began its march from Whitemarsh to Valley Forge, where they were to take up quarters for that dreadful winter of 1777-78, when the army received little food or clothing and lived in huts which they themselves had erected. On December 23, Washington wrote “We have this day no less than 2,873 men in camp unfit for duty because they are bare-footed and otherwise naked . . . numbers are still obliged to sit all night by fires.” It was not until February 1778 that Baron von Steuben reached camp and began the re-organization of the army.

Legend has it that it was on the last day of Washington’s march to Valley Forge in early December 1777 that he passed along Old Conestoga road. Legend also has it that the last night of the encampment of his troops along the way was spent in the meadow across the road from where the old marker, erected by the Converse family, stood from 1880 until 1906. On this Fourth of July, 1950, this marker will again be erected in a goodly company of those among us who will take pride in this occasion and all it represents.

(The writer is greatly indebted to Richard Barringer, secretary of the Radnor Historical Society, for much of the material incorporated in this article and to officer Russell Fleming, of the Radnor Township Police Force, for the picture made especially for use in this column.)