Just as the community of St. Davids took its name from an individual, as explained in last week’s column, so also did the community of Wayne. The stories, however, concern two people widely separated by time and circumstance.

Just as the community of St. Davids took its name from an individual, as explained in last week’s column, so also did the community of Wayne. The stories, however, concern two people widely separated by time and circumstance.

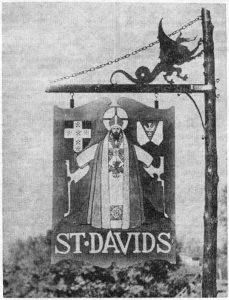

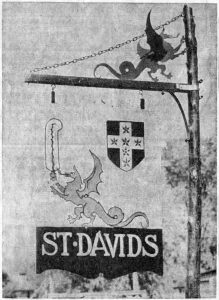

St. David, the patron saint of Wales for whom a Cathedral City in that country was named, was born in the early part of the seventeenth century, while “Mad” Anthony Wayne, one of the heroes of the American Revolution, was born in Easttown township on January 1, 1745. His old home, “Waynesborough”, still stands by the side of the road near Paoli, a stately house built by General Wayne’s grandfather in 1724, and still occupied by a descendant of the family.

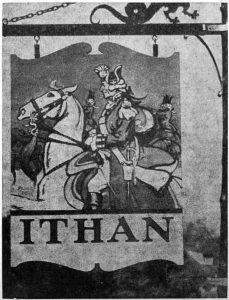

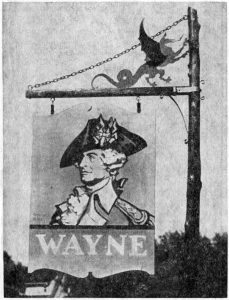

As we look at the handsome and dashing general, as pictured in the first roadside sign illustrating today’s column, we can readily agree with Amy Oakey when she says in her recent book, “Our Pennsylvania”, that, after all, “Mad” Anthony Wayne’s “madness consisted of fearlessness”. Every act of his long public career justifies that statement. The defeat of the Continental forces at Chadds Ford in the Battle of the Brandywine only gave him fresh courage to go on to Stony Point, where, on the night of July 15, 1779, he achieved the most brilliant victory of the Revolutionary War.

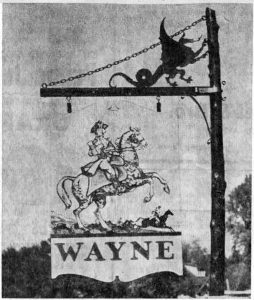

The second picture in today’s column shows Anthony Wayne on horseback as he led his troops at Chadds Ford. The two signs were designed and painted by Arthur Edrop.

The second picture in today’s column shows Anthony Wayne on horseback as he led his troops at Chadds Ford. The two signs were designed and painted by Arthur Edrop.

Wayne’s private career as a farmer in Chester County, after his marriage to Polly Penrose in 1767, was a short-lived one. When small Margaretta was six years old and Isaac three, their father was elected to the Pennsylvania Convention and Legislature, serving on the Committee of Safety. But his activities in Philadelphia were not long-lived, either. In 1775 he raised a regiment, with which he took part in a campaign against Canada. Although he was wounded at the Battle of Trois Rivieres, in January, 1776, he soon went on to the command of Ticonderoga and Mt. Independence. By September he was made a Brigadier General and had a Division at the disastrous Battle of the Brandywine at Chadds Ford. The following month he commanded the right wing at the Battle of Germantown.

For his part in the great victory at Stony Point, Wayne received a Congressional Gold Medal. Later highlights of his career were the bayonet charge by which he rescued Lafayette in Virginia in 1782 and his daring attack on the British Army at Green Springs later in the same year.

Once he had done his share in winning the Revolutionary War, Anthony Wayne retired quietly to his Chester County farm, but it was not for long.

Soon he was summoned by General Washington to take care of counter-attacks against the Indians in their frontier raids. And so, in June, 1792, Wayne moved westward to Pittsburgh and then proceeded to organize the army which was to be the ultimate arbitrator between the Americans and the Indian confederations.

The years of border warfare that led up to the Treaty of Greenville were full of hardships for both Americans and Indians. Before the treaty was fully concluded General Wayne died on December 15, 1796, in Erie, as a consequence of severe leg wounds. His mission, however, had been fully accomplished.

The reconstructed block house at Fort Erie, originally built in 1795, is now a monument to the greatness of one of America’s early generals. Here, also in Erie, was Wayne’s original burial place. Some years after his death, his son, hearing of the neglect of the grave, rode on horseback from his home in Chester county to bring back the remains for re-burial in Old St. David’s churchyard, a spot close to the birthplace of his father. Although many of the old stones in the church burial ground date back to the early 1700’s, none is so famous as that of the Revolutionary hero from whom the community of Wayne takes its name. The south front of the tall and impressive monument bears this inscription:

“In honor of the distinguished military services of Major General Anthony Wayne and as an affectionate tribute to his memory, this stone was erected by his companion in arms, the Pennsylvania State Society of the Cincinnati, July 4, A.D. 1809, thirty-fourth anniversary of the Independence of the United States, an event which constitues the most appropriate eulogium of an American soldier and patriot.”

In erecting their roadside markers in December, 1935, the Wayne Committee for Civic Progress gave outward expression to their pride and that of the community in the man for whom Wayne was named. Perhaps too, they expressed their satisfaction in the foresight of the generation that, discarding the earlier and less significant names of “Cleaver’s Landing” and “Louella”, finally chose the one that commemorates the name and fame of one of the greatest of Revolutionary War soldiers.