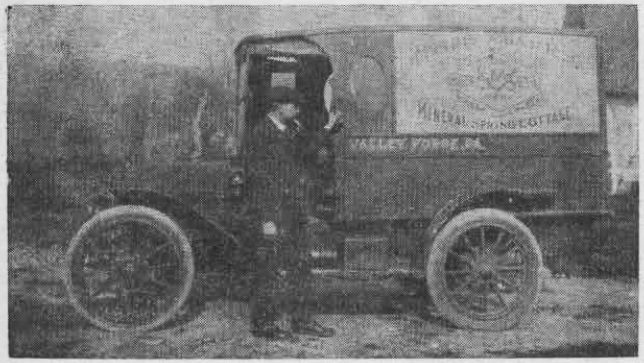

Although much has appeared in this column within the past few weeks in regard to both the mineral water und the precious stones and ores found on “Treasure Farm”, the former Morris Abner Barr property, it was not until last week that Mr. Barr made his second visit to your columnist, and told the story of how the first diamonds were discovered there.

Shortly after Colonel Henry C. Demming, consulting mineralogist, geologist and chemist of the State of Pennsylvania, had made his initial visit to Mr. Barr’s property, the latter received an anonymous letter which read in part, “Since you are the new owner or this property in Valley Forge, on Diamond Rock road, leading to Jug Hollow with that stream running through your narrow strip of woodland, you should know the following facts:

‘Every Sunday afternoon, when the sun is shining, a man enters your property on Diamond Rock road, and follows that stream all the way up to the top on Frish road. The man carries a little bag and every time the sun comes out bright and shines down through the trees onto the stream, he picks something out of the water and puts it into the little bag. Since you own this property we feel you should know this.” There was no clue to the writer of this letter except that the envelope was postmarked Valley Forge.

Thus, Mr. Barr had on his hands a mystery which he resolved to solve. Choosing the first clear Sunday after the receipt of the letter, he went a considerable way up through the woods on his property. There he found a spot which commanded a view of the full length of the stream as it ran through his land.

“Sure enough,” to quote Mr. Barr himself, “in a very short time a man entered the strip of woodland and started to follow the stream. Every time the sun would come out bright from behind the clouds and shine between the leaves over the water, the man would lean over and pick something up out of the water and place it in his little bag. This he kept up all the way until he was a short distance from me.

“As the bright sun came from behind a big cloud he seemed to spy something of exceptional interest. Hastily he leaned forward to reach into the water when his feet slipped and he went face forward and straight down the embankment. I made one leap for him and although my foot slipped, I still caught him by the arm before he landed in the water.” Mr. Ban found that the man was a cripple.

“I was mad and my Dutch blood was boiling,” Mr. Barr continued in his account. “But my conscience would no let me lay hands on a cripple.”

He realized, too, that the intruder was wise enough to recognize the value of what Mr. Barr himself had not known. These were precious stones he was picking up from the bed of the stream, and this realization came to Mr. Barr the more readily, because he had already had some intimation of the possibility of such finds from Mr. Demming.

And so Mr. Barr was generous enough to say to himself: “This man has a marvelous mind to recognize the value of these gems in the rough, lying there for all those ages, stained and winter worn as they are… it is now up to me to find out what they are.” Stone by stone, this man took from his bag what he had collected, telling Mr. Barr, as he did so, what each one was, as well as its approximate worth. Mr. Barr found that his strange visitor was a registered jeweler, born in a small community nearby and in business with his brother in a neighboring town. And so began a friendship which lasted many years, inopportune as its start had seemed to be.

From this jeweler, as well as through many other sources, Mr. Barr gradually acquired a vast store of information on precious and semi-precious stones. “However,” he says modestly, “It took me 13 years to acquire that knowledge of which Mr. Demming had first spoken, and at that I know but little of what he and my jeweler friend knew.”

After the death of the latter, his brother gave back to Mr. Barr some of the stones that still had been in the possession of the jeweler when he died. “One of these stones”, Mr. Barr writes, “was a most beautifully cut capachon, which was purchased by the Montgomery County Postmasters Association as a gift to U.S. Postmaster General Dougherty, and presented to him at a banquet when he was their guest speaker.”

Russell Conwell, president of Temple University, who became one of Mr. Barr’s staunch friends, indicated that he would like to have a jasper stone from “the land upon which George Washington and his troops encamped during that bitter winter of 1776 and 1777.” In response to his request, Mr. Barr sent him a highly polished jasper for a scarf pin. Mr. Barr is also credited with having furnished the stones for a pair of brownish black rubtile earrings, which started the popular craze for this particular type of jewelry. Mr. Barr could not fill an order for black rubtile for Masonic rings, since he did not have that particular kind among his findings at “Treasure Farm.”

Representatives from many well-known jewelry concerns came to Mr. Barr’s place, asking him “to take them to that stream swiftly rippling down through the strip of primitive woodland to see if they could find something of beauty and value.” This he often did and in leaving, they would admit that for them, “seeing had to be believing.” In closing this particular story of his strange finding, Mr. Barr acknowledges how much be owes to his crippled jeweler friend (“for sharing his great gem knowledge with me… had it not been for the true friendship or this man, all of this would never have happened.”)

(Conclusion)