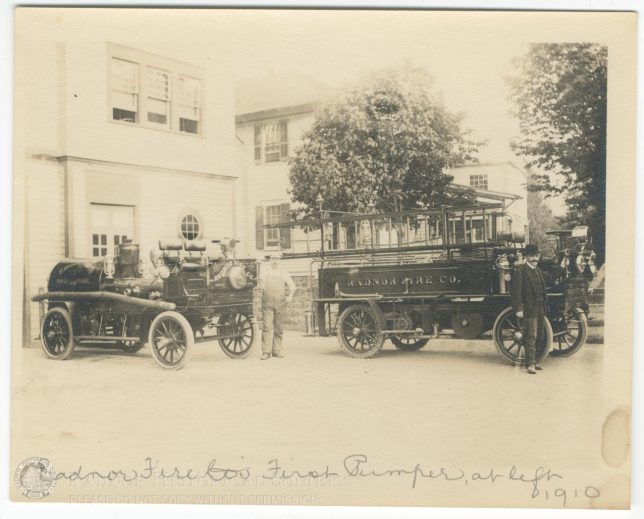

The picture illustrating this week’s column was taken in June, 1911, after the Radnor Fire Company had for several years been the proud possessor of its first two pieces of gasoline-propelled fire fighting equipment.

To the right is their first acquisition, the Knox combined automobile and hose wagon, purchased in 1906, while to the left is the Knox-Waterous automobile gas-engine of the two-cylinder, air-cooled type. The man standing a the side of the latter is a firehouseman, employed by the Radnor Fire Company for a short period to care for the new gas-driven fire engines, the mechanics of which were so little understood at that time. Although with the passing of the years his first name has been forgotten, Charles Clark remembers that his last name was Turnbull.

The man at the right was Jack Clark, remembered as “quite a town character” and no relation to our present fire chief or his family.

In the immediate background of the picture is the original fire house, as it appeared before any of the additions were built. To the right are two buildings that were landmarks in their day, although each is but a memory now. The first is the Coffee House, while next to it is the first Radnor township school building to be erected on the large plot of ground now owned by the School District.

The Coffee House was first built as a meeting place for the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. Later it was turned into the Coffee House still remembered by some of the pupils of Wayne School of an earlier era for the excellence of the soup it served. Many others ate there, including Wayne’s business men and drivers of the many horse drawn trucks on Lancaster Pike. The use of the building was given without rent by a well-known local resident, as long as no intoxicating liquors were sold in the township.

Before the Wayne Neighborhood League occupied its present quarters on West Wayne avenue, it was also housed in this building, which was not destroyed until its site was needed for the first unit of the present High School building, erected in 1923.

So much for this quaint old picture, which is all the more valuable now since the two fire engines themselves gradually rusted away on the vacant lot back of Lienhardt’s store. Since the engine purchased in 1906 was the first piece of motorized fire fighting equipment to be put into operation in the United States, it might well have found a permanent place in the Smithsonian Institute, or similar sanctuary, along with its sister engine acquired in 1908.

There is only one relic of Radnor Fire Company’s first engine still in the Company’s possession. That is the bell which was once attached to the front of the old chemical and hose wagon. It now hangs on the upstairs wall of the fire house and is sounded to call meetings to order.

In discussing the disastrous Wayne fire which really sparked the movement to obtain good fire protection in Radnor township, A. M. Ehart, editor of “The Suburban”, told your columnist of the early morning blaze which totally destroyed his newspaper plant in the early morning hours of Saturday, February 10, 1906.

The building was a pleasant, two-story, yellowish-red brick edifice on the site of the present Allan C. Hale building, and was entirely occupied by “The Suburban”. No one ever really knew the origin of the intense blaze which left nothing standing except a few foundation bricks, as shown in the picture on the front page of “The Suburban” of February 16, 1906. All had been well as far as Wayne’s night watchman knew when he stopped by at 4:00 A. M. to light the gas under the linotype machine. The shrill warning of a Pennsylvania Railroad engine as it went past on the tracks to the rear of the building gave the townspeople the first warning of the blaze.

When Wayne’s horse drawn fire engines arrived on the scene, they found that the fire had gotten a tremendous start in the corner of the building where the linotype machine had stood. Although the Bryn Mawr Fire Company engines were also called into action they arrived late, as they could make but little time over bad roads. The loss was a total one, even tot he files of “The Suburban”, which could never be replaced.

At the same time the “Suburban” building was burning, Frank Heuslein’s harness shop, which stood to the east of it, caught fire, with much loss to the contents of the shop as well as to the living quarters of the Heuslein family. The site of the shop is now occupied by Peter diBlaio, antique dealer.

By the Monday morning following the disastrous Saturday “The Suburban” had resumed operation of its paper from the Downingtown plant, where it continued until 1916, when it occupied the Maguire Building, where it is now located. While the printing was done in Downingtown, the business of the newspaper was carried on in an office formerly occupied by Dr. J. C. Ward, with the still-familiar Wayne 123 (0123) as the telephone number. The Heuslein Harness Shop was also able to resume business shortly after the fire.

This February 16, 1906, edition of “The Suburban”, under the headline of “Steps Being Taken for the Organization of a First Class Fire Company in Wayne–Prominent Men Back of Movement”, tells of a meeting held on the Tuesday evening following the fire, which was attended by many of the foremost citizens of Wayne and St. Davids. The article also goes on to state that “subscriptions were being procured for the purchase of a modern combination chemical and hose truck similar to the one used by the Bryn Mawr Company, plenty of hose and all the equipment needed to fight fires successfully. Stringent rules have been made and enforced.

This then was the actual beginning of our present efficient Radnor Fire Company, in the formation of which “the three Charlies” figured so prominently – Charles Wilkins, Charles Clark and Charles Stewart.

(To be continued)