Two recent columns of “Your Town and My Town” have been devoted to a review of a quaint old book, “The Old Main Line,” as written by J.W. Townsend 1919. This week’s column will deal with outdoor sports, although they were practically non-existent then as compared to their present day form.

Back in the 60’s, according to Mr. Townsend, football, basketball, hockey, golf, squash and tennis were still unknown. In the late 60’s, “a so-called bicycle appeared… the rider sat on top of a wheel about five feet high with a little wheel to steady it. Woe to him if he struck a stone, as he took ‘a high header’… a man was indeed killed in this way on Lancaster Pike. When the present form of bicycle came years later, with low wheels and rubber tires, they were called ‘safeties.’

“Tennis did not appear until the late 70’s, and although baseball was played in some places it was little known in the suburbs. Cricket came into existence at about this time… the Merion Cricket Club had just been organized. Quoits were played occasionally.

“But the universal game of the 60’s for adults and children was croquet. Hours were devoted to it, and although there was little exercise in it, at least it kept people out-of-doors… on Sundays the gentle croquet mallets rested peacefully in their box.”

“Playing cards were strictly taboo among the Quakers and Presbyterians, who largely predominated in Philadelphia’s social life. Youngsters played parchesi, jackstraws and lotto, while their elders joined in on checkers and backgammon. Billiards and chess were other popular games.

In the late 70’s, when Louella House, in Wayne, became a summer hotel for Philadelphians under the name of Louella Mansions, its owners issued a little booklet setting forth its attractions. Its Casino contained shuffle-boards, a pool table and gymnasium apparatus. The mansion itself contained library, smoking and music rooms, orchestral music every Saturday evening with extensive room for dancing. So, even in a decade or two, popular summer hotels of the Main Line began to offer more in the way of amusement than did the boarding house of the ’60’s.

“Country summering” was becoming increasingly popular with city folks, as indicated by a small prospectus issued by the railway company in 1874. It listed 54 boarding houses from Overbrook to Downingtown with accommodations for 1,330 “quiet guests,” exclusive of the Bryn Mawr Hotel, which held 250. “The Main Line showed the first symptoms of getting gay,” writes Mr. Townsend, “when the Summit Grove Hotel, in Bryn Mawr, got well under way in the summer of 1873. The Bryn Mawr assemblies were the events of the season, with about 500 people attending each of them.

“Other entertainments of the summer were a magic lantern exhibition by Will Struthers; a comic talk by Benjamin Franklin Duane, a mock trial and an Orpheus Club Concert… It is curious to consider that these functions continued through the whole of hot summers… Philadelphians had not yet acquired the expensive and unnatural habit of seeking distant climes for cold in summer as well as for heat in winter.”

Mr. Townsend’s account continues, “The hotel life was quite similar to that of the old boarding houses, only it was gayer and more formal… In the afternoons nearly everybody drove or rode. Cavalcades of perhaps 25 riders would go out together and explore the country roads for miles around. Women and girls used only sidesaddles… the Radnor Hunt had not started and little hunting or jumping was indulged in. The roads were all dirt roads except Lancaster Pike, which was very rough and ridgey, without any smooth surfacing. The dirt roads were fine for horseback, but became a foot deep in mud when it rained, and in winter were almost impassable. The old Haverford road that ran through the Whitehall district was then a “plank road,” that is, one half of it had boards laid close together, unpleasant to ride on but a great boon in muddy weather.”

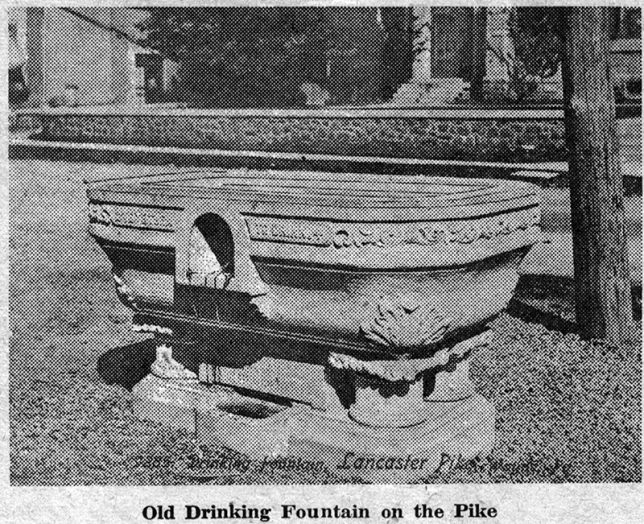

When the Bryn Mawr tract was laid out, its avenues were covered with a coarse gravel, which made for very slow travel. These roads exasperated Mr. Cassatt, vice-president of the railroad who was fond of driving his four-in-hand coach. He accepted the position of Township Road Supervisor and was instrumental in obtaining macadamized roadbeds. He also got a company of his friends to buy Lancaster pike as far as Paoli and to make a macadamized road of it. Toll was charged to keep it in order and “it was a boon” to the driving public for many years. In later years the toll gates were abolished, when the State bought the Pike and maintained it by taxes.

Next week’s column continues with more excerpts from Mr. Townsend’s book, in particular concerning the dress of the Main Line men and women in the 60’s. Other matters to be described range from transportation to lightning rods.