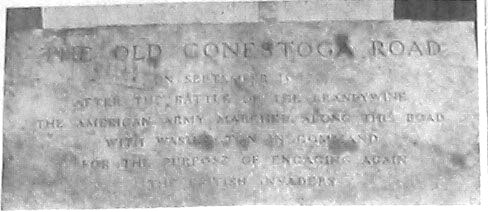

As we told you in last week’s column, the second Spread Eagle Tavern, built on the site of the first quaint small structure, was completed only a year or two after the Lancaster turnpike was finished, the first stone turnpike to be constructed in the United States. The tavern immediately sprang into great popularity, since its furnishings and cuisine were perhaps unsurpassed in the entire State of Pennsylvania. During the summer and fall of 1798, when yellow fever raged in Philadelphia, the inn was crowded with members of the Government, as well as attaches of the accredited representatives of the foreign powers in Philadelphia.

As early as 1730 and thereabouts small settlements began to spring up around roadside taverns, since it was there that elections were held, and much of the entertainment of the community centered. These villages were often known by the tavern sign until they were large enough to have a name of their own. So it was with the neighborhood of the Spread Eagle as a hamlet of some size grew up around it. In addition to the usual blacksmith and wheelwright shops, livery stables, barns and other outbuildings attendant to an inn of the first rank, there was a village cobbler and tailor.

For many years the large “Eagle” store on the opposite side of the turnpike did a flourishing trade. Soon a post office was located in the little hamlet which became known on all local maps of the day as “Sitersville.” In 1795, Martin Slough started to run a four-horse stage between Philadelphia and Lancaster which proved so popular that a number of other stage coach lines were soon in operation.

Because of its distance from the city, the Spread Eagle became the stopping place of not only the mail and post, but also for meals and relays, as it was the first station west and the last relay station eastward on the turnpike. Stages usually left Philadelphia at four or five o’clock in the morning and stopped for breakfast at this well known hostelry. In 1807, stage passengers were charged 31 1/2 cents per meal, while others were charged 25 cents. The reason given for this discrimination was “that being obliged to prepare victuals for a certain number of passengers by the stage, whether they came or not, it frequently caused a considerable loss of time, and often a waste of victuals, whereas in the other case they knew to a certainty what they ahd to prepare.”

At this period it cost twenty dollars to travel by the stage from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh, with an extra charge to twelve and a half cents for every pound of luggage beyond fourteen pounds. Meals and lodgings for the 297 mile trip cost in the neighborhood of seven dollars. It took about six days to complete the journey. By wagon it took twenty days or more, with five dollars per cwt. for both persons and property charges. Other expenses along the way amounted to about twelve dollars.

As to liquid refreshment dispensed over the bar and drunk by hardy “wagoners” and travelers in those early days, it consisted mostly of whiskey, brandy, rum and porter. There was also “cyder,” plain, royal or wine; apple and peach brandy and cherry bounce. A bowl of good punch was always in order among the better class of stage travelers.

John Siter, during whose ownership the new tavern was built, was succeeded by Edward Siter. Later James Watson took over for a period of two years. Since he was not successful in the venture, ownership reverted back again to Edward Siter, who remained in charge of the inn until the year 1817. During his temporary retirement from the Spread Eagle, Edward Siter conducted a grocery store in Market Street in Philadelphia, as witnessed by the following notice in the “Federalist” of December 8, 1812.

“Edward Siter

Late of the Spread Eagle on the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike road, takes the liberty of informing his friends and the public in general that he has taken that large store on South East corner of Market and Eighth Sts., Number 226, in Philadelphia, where he is now opening a good assortment of groceries, wholesale and retail on the most reasonable terms, where country produce will be bought or stored and sold on commission with punctuality.

He believes himself from his former conduct in business to obtain a share of publick patronage.”

From 1817 to 1823, David WIlson, Jr., was “mine host” at the Spread Eagle. From 1823-1825, Zenas Wells kept the Inn. In a short time during this period the original signboard representing the American eagle was changed by a local artist who, as told in last week’s column, added another neck and head to “our glorious bird of freedom.” Perhaps this change was due to some ripple of political excitement rife at that time. Be that as it may, the new signboard caused so much merriment that in 1825 it took on its old form again. Neighbors and wagoners could not see the utility of the first change, and in derision nick-named it the “Split Crow.” For a time the tavern was even referred to by that name. After it was again Americanized in 1825, it was repainted many times as the changing seasons took their toll of fresh paint. Finally, when the usefulness of the old building as a tavern passed away, the eagle which had for so many years stood as the sign post on one of the finest taverns on the Lancaster Turnpike was finally effaced by the action of the elements.

(To be continued)

For her information the writer is indebted to the book, “Early Philadelphia – Its People, Life and Progress,” by H. M. Lippincott and J. B. Lippincott, and to “Wayside Inns on the Lancaster Roadside,” by J. F. Sachse.