In the year 1954, nearly 80 years after the Centennial was held in Philadelphia, it is indeed a rare occurrence to talk to anyone whose childhood recollections reach back to one of the greatest celebrations that the city has ever known.

In the year 1954, nearly 80 years after the Centennial was held in Philadelphia, it is indeed a rare occurrence to talk to anyone whose childhood recollections reach back to one of the greatest celebrations that the city has ever known.

George W. Schultz, an old-time resident of Wayne, who is now residing in the Anthony Wayne apartments, is one of the few people who really remembers the Centennial.

One day after your columnist had thanked Mr. Schultz for the loan of the handsome Centennial Portfolio, from which the picture of the Japanese Building was reproduced for last week’s column, he wrote a note in reply, part of which read:

“Yes, the Centennial Album is a rare thing now… I was 11 years old that year (1876) and well recall the main buildings and their contents, as my father took my brother, Lewis, and me out there two or three times. The Horstman firm (5th and Cherry streets) of which my uncle and he were both members, had a loom on exhibition, turning out small silk pictures of Independence Hall and of Masonic Hall, which they sold as souvenirs. These pictures, about 6” x 10”, were woven in colors.

“The foreigners working on their buildings were very strange to us – such as the Japanese and Chinese in costume with wooden clogs, sandals, etc… Also there were Dutchmen and Turks.”

It is interesting to compare Mr. Schultz’ recollections with the notes given in the Centennial Portfolio, not only in connection with the picture of the Japanese building in last week’s column, but also with those of another building known as the “Japanese Dwelling.” This house, during its erection, created more curiosity and attracted more visitors than any other building on the grounds. It was erected by native Japanese workmen, with materials brought from home and built in their own manner with curious tools and yet more curious manual processes. In fact the whole work seemed to be executed upon exactly reverse methods of carpentering to those in use in this country.

The building was put together without the use of iron. The different parts were mortised, beveled, dove-tailed and joined, and when it was necessary to use any other fastenings, wooden pins were employed. The woods are of fine grain, carefully planed and finished, and the house, which is the best built structure on the Centennial grounds, was as nicely put together as a piece of cabinet work.

So much for the “unique building” which was “one of the most noted curiosities of the exhibition.” While the information does not apply directly to the other Japanese building, from parts of which the Strafford railroad station was built, it is still both interesting and pertinent in that the two buildings were erected by the same group of Japanese artisans.

The “Japanese Bazaar”, as the Japanese building which we pictured last week was sometimes called, was built in order to create a market for articles less elaborate and less expensive than those sold in the Japanese section of the Main Building. When the Centennial opened, the “Japanese Bazaar” housed many thousands of these artistic, low priced souvenirs of the Centennial.

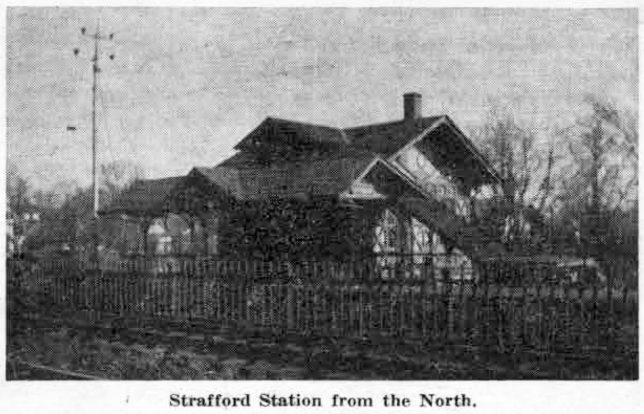

Perhaps only the most imaginative among the Philadelphia commuters waiting at Strafford station for the eastbound Paoli Local can even envision the fact that the lumber that has gone into the construction of the station could ever have helped to house the exotic Japanese collection. This lumber was, evidently, not originally designed for exterior walls, since there were none. The Portfolio describes the interior of the building as “a series of counters, shelves and tables, open to the air and light, protected only by the roof. The latter is in the usual Japanese style, covered with black tiles, those at the edges being painted black.”

The small piece of ground which surrounded the building was “fixed up in Japanese garden style with flower beds laid out neatly and fenced in with bamboo. Screens of matting and of dried grass divide the parterres… the garden statuary is peculiar. Bronze figures of storks six to eight feet high stand in groups at certain places, and a few bronze pigs are disposed in easy comfort in shady places.” Again, the imagination of the commuter must be called into play as he looks up to see the electric engine of his approaching “Local” with nary a sign of bronze pig or even a bronze stork on the landscape!

But even with these exterior decorations left on the Centennial grounds, the wonder still remains that the lumber once used in the construction of the Japanese building at the Centennial could have gone, first into a station, located at Wayne, which was later demolished and then the lumber again put to use in the present passenger station, as well as the shelter at Stratford. And the suggestion of the original Japanese architecture still survives these changes and the wooden pegs are there for all to see!

[Ed. Note: More recent research has refuted the claims that Strafford train station originated at the Centennial. Confirmable documentation shows that the station was built first in Wayne in 1873, and was moved to Eagle (now Strafford) ten years later.]