The large, well-worn family Bible of the Martin family, which was lent to this writer by Mrs. Emily Siter Wellcome in order that the history of original members of the family, who owned Martin’s Dam, might be traced back to England, was a repository of various newspaper clippings, several dating back almost sixty years, others not so old.

Among these are several issues of “The Suburban” containing a column headed “Historical Notes” with the sub-heading “Reminiscences of the Neighborhood of Wayne and Strafford in the Early Part of the Last Century”. This would give evidence that more than half a century ago “Your Town and My Town” had a predecessor in “The Suburban”.

Allthe newspaper clippings in the old Bible were not of an historic nature, however. Three of them have to do with an event of such contemporary interest at the time they were published, that it was given much space in the “Evening Bulletin” of December 21, 1897, in the “Philadelphia Inquirer” and in the now defunct “Morning Ledger” of December 22. This was a fox hunt given by the Messrs. Siter and Barrett, of Wayne, on December 21, for which over 200 invitations were issued, and at which “many of the foremost huntsmen around Philadelphia were present on their best mounts to join in the lively chase after Master Reynard”. In addition “75 hounds filled the air with strains that delighted the huntsman’s ear.”

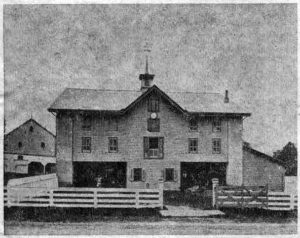

Mrs. Wellcome explained that these particular clippings were of sufficient interest to form part of the Martin family history, since her mother, Miss Sally Martin, married William Siter, one of the two hosts at the famous fox hunt of which we are writing. The livery stable of Siter and Barrett was located slightly to the rear of the present Buick agency building. It later became the Kromer livery stables.

The “Bulletin” devoted almost a column to this event, which took place around “the snow-clad hills of Wayne” and which was participated in by the Radnor, Rose Tree, Royersford, Gulph Mills, Phoenixville, Lower Merion and Strafford hounds. Before the hunt “a stand-up breakfast of excellent cheer was given by Messrs. Siter and Barrett in the large carriage house in the rear of their livery stable. The whole place was prolfusely decorated with laurel branches, and a regular old-fashioned time was indulged by the pink-coated huntsmen preparatory to the start.”

Breakfast over, Mrs. William Barrett liberated the fox in the field in front of the livery stable just across the Lancaster Pike. She was immediately presented with a handsome bouquet of American Beauty roses as the fox, to the shouts and yells of several hundred spectators, sped rapidly away in the direction of St. Davids.”

A vivid description of subsequent events then follows. “Twenty minutes later”, according to “The Bulletin”, “the blast of a bugle rang out merrily on the morning air. In an instant came the answer from the seven packs of hounds fastened up in the stable. It was one joyous yelp. At the same moment the doors were thrown open and away they dashed across the pike to find the scent. No time was lost. A young English hound imported by Charles E. Mather for the Radnor Hunt Club gave lip, and away it sped in the direction the fox had gone, followed by the combined packs.

“The sight was an inspiring one, and many many a looker-on sigh for a moment as the pink-coated huntsmen dashed across the meadow, right in the wake of the hounds. The atmosphere was filled with music, and as hunters and hounds disappeared over the brow of the hill, it was as if the light had gone out where a minute or two before all was gladness and pleasurable excitement.”

The chase that followed was a memorable one in the annals of “that far-famed fox-hunting country around Wayne.” It was, however, a brief one, since it was only 45 minutes after the fox was liberated that it was run to earth within three miles of the starting point, on the farm of Mrs. Ramsey, and just at the back of St. David’s Church. The chase had led over the farms of Joseph Childs and Thomas Watson to Newtown Square, after which it circled back toward Wayne.

Brief in time though it was, this chase was still a good one while it lasted, according top our “Bulletin” reporter. The latter describes it as “much faster than the ordinary Pennsylvania fox hunt… it partook of the character of a Melton Mobray Meteon, one of those swift Lancastershire hunts in England that try the mettle of man and horse… The country over which the fox made his tortuous course was well calculated to arouse the fearless instincts of the followers oi the chase.

It was up hill and down dale, through scrub and brush and dense woods frosted with silver and dangerous to the riders. The wet snow balled under the horses’ feet, and rendered jumping dangerous, but to such old-timers as Edward Crozer, Lemuel Altemus, Frank Barrett, David Sharp and a few other well mounted huntsmen, the element of danger only lent an additional pleasure to the chase. Some jumps were made from slippery rising places that would have brought down the wildest applause had they been made before a Philadelphia or New York Horse Show gathering.”

The honor of being first at the finish fell to John Torpey, of Radnor, who was mounted on “Plunger”. Secvond to reach the scene was Master Billy Holloway, of Wayne, on his imported Irish pony, “Connemarra”. Among other well mounted riders were Lemuel Altemus on “alonzo”, David Stevenson on the imported Canadian hunter, “Gold Blade”; Edward Crozer on “Peter” and Frank Barrett on his bay mare, “Aggie”. John Mather, of Wayne, was master of the hounds.

The quarry was a handsome dog fox holed a short time previously by John Torpey and Wallace Henderson, master of the Gulph Mills hounds. It was presented by them to Messrs. Barrett and Siter after it had been captured at Easttown near Paoli. “It was”, according to our reporter, “perhaps an oversight on their part that they did not anticipate Master Reynard would make his old diggings by closing up the entrance on Mrs. Ramsey’s farm, which communicated with the burrow at Easttown.”

Among the several hundred participants and spectators of the hunt were many well known in Wayne, among them Dr. and Mrs. Joseph Egbert, Dr. and Mrs. C.W. Smedley, Mr. and Mrs. I. Walter Conner, Mr. and Mrs. Frank Smith, Mr. and Mrs. William Siter, Penn Smith, Henderson Supplee; John, Mason and Nathan Pechin’ Frank Barrett, Thomas Fleming, Christopher Downes, D.B. Turner, Samuel Altemus, H.B. Hare, William Rowan, Paul Lamorelle, Mr. and Mrs. Frank Dallett, Andrew Sellers, Harry Childs, Joseph Childs and Joseph Childs, Jr., Millord Pugh and many others.

Still others came from as far away as New York, while more nearby localities such as Philadelphia, Phoenixville, Duffryn Mawr, Gulph Mills, Devon, Media, Berwyn and Merion Square were well represented. December 21, 1897, must indeed have been a gala occasion in Wayne!

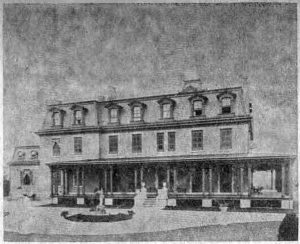

The cottage, which was occupied by the Askin family during the period when the more pretentious Louella Mansion was under construction, stood well to the northeast of the latter, with its back to the railroad. The small summer house was located between the Cottage and the Mansion.

The cottage, which was occupied by the Askin family during the period when the more pretentious Louella Mansion was under construction, stood well to the northeast of the latter, with its back to the railroad. The small summer house was located between the Cottage and the Mansion.