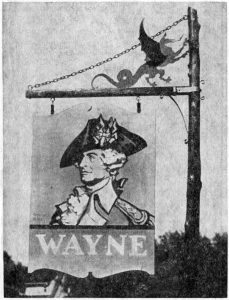

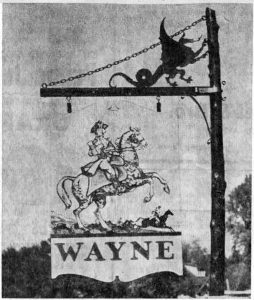

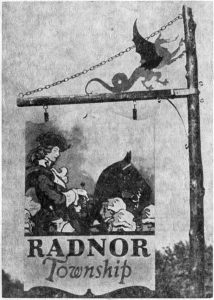

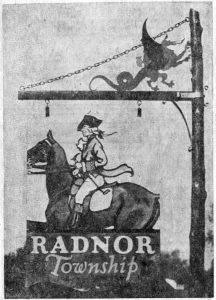

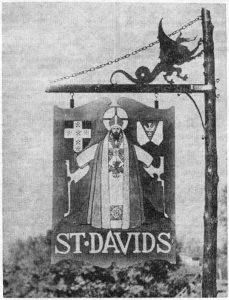

The roadside signs shown in today’s column are two of the eight presented to Radnor township by the Wayne Committee for Civic Progress in December, 1935.

The roadside signs shown in today’s column are two of the eight presented to Radnor township by the Wayne Committee for Civic Progress in December, 1935.

Both were hung on standards on the Lancaster highways and marked the boundaries of St. Davids, just as the two shown in last week’s column marked the boundaries of the settlement of Ithan, along Conestoga road. As stated in last week’s column, all eight were from designs made by Arthur Edrop. The two shown today were painted by Wayne Martin, at that time an art instructor in Radnor High School.

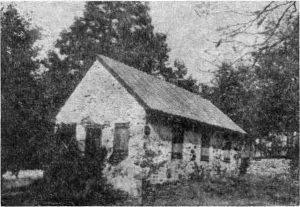

Since Radnor Township was originally a Welsh settlement, it is natural that the name of the patron saint of Wales should be perpetuated in the community, notably in the little Episcopalian Church, “Old St. David’s”, founded very early in the 18th century, and also in the community of St. Davids, lying to the east of Wayne. Separate in name only, the two form a continuous whole, with Pembroke avenue as it runs north and south at right angles to Lancaster Pike, a boundary line that is perhaps not generally known.

Most impressive, indeed, is our good patron saint as he is shown in all the glory of his ecclesiastical robes, with his personal coat of arms and the device of the Seal of St. David.

David, or “Deii”, patron saint of Wales, born about 601 A.D., is, according to tradition, the grandson of Ceredig, king of Cardiganshire. According to the “New Standard Encyclopedia” (Funk and Wagnalls) he was “educated by monks and founded monasteries, in particular the one at Menevie, now called St. Davids, in Pembrokeshire, where he became abbot, which office was equivalent to bishop… and his shrine became a favorite place of pilgrimage. He was canonized in 1120. His festival is held on March 1.”

The cathedral village-city of Pembrokeshire, known as St. Davids, is situated near the sea to the southeast of St. David’s Head, the most westerly promontory of South Wales. According to the encyclopedia this little town, locally known as “the city”, stands in a lofty position near the cathedral close, and consists of five streets focusing on the square, called Cross Keys, the ancient market place still possessing its market cross.”

Even in pre-Christian times this general locality seems to have been an important one, being on the route frequented by pre-historic traders from the Mediterranean to Ireland. As their small boats were driven hither and thither by the wind and the tide, they had their alternate landing places along the coast of Wales.

The encyclopedia continues its account by saying that “the pre-Christian tradition was continued by the Celtic saints moving between Ireland and Wales… The little landing places on the shore now had Christian chapels, where prayers were possibly said for safe voyages. At a focus behind a group of these small ports, in the quiet, sheltered, well watered valley of the Alun, the fine cathedral of SS. David and Andrew was built. Throughout the middle ages the cathedral was the center of pilgrimages. Two pilgrimages to St. David’s were popularly thought to equal one to Rome itself.” This old cathedral was restored in 1862-78, and is now the most important and interesting church in Wales.

And so, deep-seated in history is the origin of the name of one of the oldest churches in Radnor township, and of one of its smaller, but still important communities.

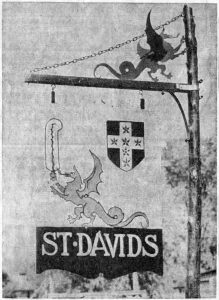

Our second illustration, according to its originator, Arthur Edrop, is “an heraldic arrangement, including the name of St. Davids in Wales and the Welsh dragon holding an ostrich feather, as he did on the shield of Arthur Tudor, Welsh prince”. This same decorative dragon is repeated atop the bar of oak which protrudes at right angles from each of the eight posts of red cedar which support the highway signs. As their contribution to the project, the Edward G. Budd Manufacturing Company, of Philadelphia, cut these dragons from “Everdue”, which was donated by the American Brass Company.

Our second illustration, according to its originator, Arthur Edrop, is “an heraldic arrangement, including the name of St. Davids in Wales and the Welsh dragon holding an ostrich feather, as he did on the shield of Arthur Tudor, Welsh prince”. This same decorative dragon is repeated atop the bar of oak which protrudes at right angles from each of the eight posts of red cedar which support the highway signs. As their contribution to the project, the Edward G. Budd Manufacturing Company, of Philadelphia, cut these dragons from “Everdue”, which was donated by the American Brass Company.

(to be continued)