Of the eight roadside signs which were presented to Radnor township by the Wayne Committee for Civic Progress in 1935, six have illustrated recent columns of “Your Town and My Town”.

Of the eight roadside signs which were presented to Radnor township by the Wayne Committee for Civic Progress in 1935, six have illustrated recent columns of “Your Town and My Town”.

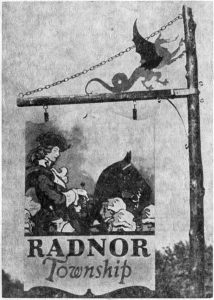

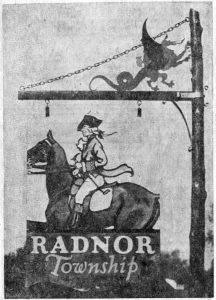

The final two of the series, as shown in today’s column, are those marking the limits of Radnor township along Lancaster pike. One, placed near County Line road as it crosses the Pike at the bottom of the Rosemont hill, marked the eastern boundary, while the other stood on the Pike near the Covered Wagon Inn to mark the western boundary. Two others showed the boundaries of St. Davids, while two more did the same for the Wayne district. All of these were along the Pike while the remaining two of the series were on Conestoga road to mark the boundaries of Ithan.

The first picture shown in today’s column has been named “the Toll Gate” by Arthur Edrop, the artist who designsd and painted it, while the second is called “Old Lancaster Pike”. The first is one of the most attractive of the eight in the series, showing, as it does, a fair equestrienne in a riding habit typical of the late 1700’s. Sitting very erect on her spirited black horse, her riding crop in her hand, the lady is apparently receiving homage from four of her admirers. Whether they were awaiting her at the toll gate, or just happened by, is not quite clear in the picture’s title.

The word “toll” dates back through the centuries, a word of Greek derivation originally meaning “something counted”. Later, as tax collectors had to count sheep and many other things, the idea of counting became associated with taxes. At first any kind of tax was a “toll”, although later it was only a special tax as defined above.

During the 18th and 19th centuries it was a word that every traveller over the turnpikes of America came to know. Toll gates were placed at regular intervals along the roads to halt passing horsemen or vehicles. These gates were raised only after the traveller had paid a toll, the amount of which varied, that for the man on horseback being about five to ten cents, and possibly twice that sum for a team and a wagon. The proceeds of this tax were used to pay for road repairs, such as they were, in those early days of travel along the highways of America.

During the 18th and 19th centuries it was a word that every traveller over the turnpikes of America came to know. Toll gates were placed at regular intervals along the roads to halt passing horsemen or vehicles. These gates were raised only after the traveller had paid a toll, the amount of which varied, that for the man on horseback being about five to ten cents, and possibly twice that sum for a team and a wagon. The proceeds of this tax were used to pay for road repairs, such as they were, in those early days of travel along the highways of America.

Our own Lancaster pike, as it goes through Radnor township, is the first stone turnpike in the United States. Replacing the old Conestoga road which connected Philadelphia with Lancaster, construction on it was started in 1792 and finished in 1794 at a cost of $465,000, financed by a private company. Along its 62 miles, between Lancaster and Philadelphia, there were originally nine “toll bars”, beginning two miles west of the Schuylkill River. To the many German travellers who passed along this early stone turnpike, these toll stops were known as “Schagbaume”.

John T. Faris, writing in “Old Roads out of Philadelphia”, tells of “the Conestoga wagons, stages, pack horses and private conveyances that at times made an almost continuous procession” along Lancaster highway. He writes, too, of a traveller of 1810 who relates, “at the toll gates the keepers were usually busily engaged in taking the toll, for sometimes three or four conveyances stood in waiting. Some of the gatekeepers kept tally on a slate of the money they took in. Coming early to a toll gate we had to wait until the sleepy keeper, rubbing his eyes, came out for our toll. Generally, these gatekeepers were taciturn, sour looking men. Indeed, they seemed to me to resemble each other so much that I almost believed them to be of one family, sons of one father.”

This same author tells of difficulties with travellers who sought to escape the payment of toll. Finally a provision was included in the act of incorporation “for the fining of any one who should pass a toll gate without paying the required fee, or who should evade payment in some other way.”

Writing in “The Old Main Line”, J.W. Townsend tells of later days in the history of toll gates in this immediate vicinity. All the roads in the early 1870’s in the Bryn Mawr section were dirt, except Lancaster pike “which was very rough and ridgey, without any smooth surfacing”. When Mr. Cassatt, then vice-president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, who “was fond of driving his four-in-hand coach” was finally prevailed upon to accept the position of township road supervisor, things changed for the better.

He was not only instrumental in obtaining macadamized roadbeds on Bryn Mawr roads, but he got a company of his friends to buy Lancaster pike as far as Paoli, in order to make a macadamized road of it also. Toll was charged “to keep it in order… and it was a great boon to the driving public for many years.” When the pike was purchased by the State in later years the toll gates were abolished, as all state owned roads were maintained by taxes.

Many residents in this vicinity remember those toll gates which, as a matter of fact, were not abolished until some years after the turn of the century. A picture of the small cottage which once served as a toll house at the northwest corner of Lancaster pike and Chamounix road illustrated this column in the October issue of “The Suburban”. Another house, which is said to have served as a toll gate along the Pike in Revolutionary days, is the small white stone house just to the west of the Spread Eagle Mansion, on the Pike in Strafford. Standing as it does just at the line of the roadway itself, it is a very likely spot for a toll house.