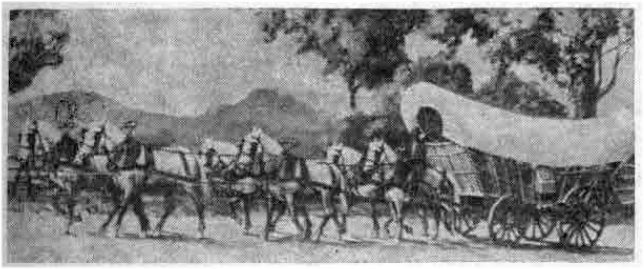

Many times during the past few weeks, as your columnist has turned the pages of John Omwake’s book “Conestoga Six-Horse Bell Teams”, which she has used as a reference in this present series of articles, she has wished that she might share its beautiful illustrations with all of her readers, especially the frontispiece, which shows an outstanding example of a large Conestoga wagon, with its six-horse bell team.

From one of the column’s interested Wayne readers has come a picture so like this frontispiece that only a close inspection of the two shows the slight difference between them. The picture has been lent by Mrs. Norman H. Dutton, of North Wayne avenue, for use in this column. The original was one made in 1843 of her great-grandfather, Jacob Eby, as he made one of his many trips between Pittsburgh and Baltimore in his covered wagon.

From one of the column’s interested Wayne readers has come a picture so like this frontispiece that only a close inspection of the two shows the slight difference between them. The picture has been lent by Mrs. Norman H. Dutton, of North Wayne avenue, for use in this column. The original was one made in 1843 of her great-grandfather, Jacob Eby, as he made one of his many trips between Pittsburgh and Baltimore in his covered wagon.

In 1849, Jacob Eby put his son, Dabid Eby, “on the road to wagon”, which employment he “continued at intervals until the Pennsylvania Railroad was completed in 1853, and then for five years more at ‘piece’ wagoning to intermediate points between Chambersburg and Bedford.”

“Looking back to the years thus employed”, David Eby writes in his booklet, “Retracing of the Famous Old Turnpike”, “I consider them as the palmy days of my life.” And so intense did his longing become in later life to go over the famous old turnpike once more that in 1908, when he was “on the shady side of 77”, he undertook the trip between Chambersburg and Pittsburgh on foot.

This, he decided, was the best way to “relocate old tavern stands, and secure such other information as would help to make a narrative of the days of wagoning.” Not counting the Sunday on which he rested, Mr. Eby made the trip of 150 miles in seven and one-half days, an average of 20 miles per day.

In the 1840’s and early 1850’s when the younger wagoner, David Eby was making regular trips between Chambersburg and Pittsburgh, there was an average of a tavern for each mile. When he retraced his way by foot in 1908, he found that “most of the old taverns not as such, but as dwellings, are to be seen… the old signs are down, the wagon yards are enclosed, and the barrooms where the wagoners congregated are converted to a better use.

“These wagoners were a noisy, jolly set who loved the frolic and dance. To the music of a violin the performer suited its action to whatever was called for, ‘The Virginia Reel’, the ‘French Reel’, ‘Four Square’, ‘Jim Crow’, or ‘Hoe Down’ being the popular rage. The fun was fast and jolly, especially when they imbibed too much of ‘Monongahela’ at three cents a drink.”

Of the contrast between past and present as he saw it, Mr Eby comments, “In my mind the automobile drivers are not regarded with the same distinction as were the stage drivers whose lordly swing and handling of the ribbons made them – at least in their estimation – the aristocrats of the times. In the barroom they were the center for the admiring crowd, who were always ready when ‘asked up’ with the condescending reply, ‘yes, with a little sugar, please’!”

The picture of the Eby Conestoga wagon, as it looked on the road in the middle 1800’s, illustrates in a striking manner the descriptions Mr. Omwake has given of the vehicles that were sometimes called “Ships of Inland Commerce” as they “cruised with their great white tops between the green Pennsylvania hills.” The long deep wagon beds with the sag in the middle and the white top are indeed somewhat reminiscent of boats with their sails. The six-horse team of dappled grays – always a favorite color with Pennsylvania wagoners – shows the bell hoops on each of the six horses, including that on which the driver rode. In many cases this was not used, since it interfered with the driving of the horses. The lead horses wear hoops of five bells, the middle pair have four and the last pair three. The six horses are obviously of the strong, sleek, heavy-set type, described in last week’s column as typical of the Conestoga horse. Their handmade harness is strong and heavy.

The box on the side contains tools, which were necessary for emergencies along the road. Among the tools were pincers, tongs, wrench, bolts, nails, open links and straps. Much of the “ironing” of the lids of these tool boxes was most ornate, being fashioned by smiths who had learned this trade. Protruding from the wagon, just below the tool box, is seen the “lazy board” on which the driver stood when he was not guiding his team from the back of the saddle horse, or walking beside the wagon.

Not clearly shown in the picture is the “tar pot”, which was as essential to the successful progress of a trip as was the tool box. A tar pot contained the pine tar for lubricating the axles and the green beds. When it became necessary to do this, a heavy wagon jack, made especially for Conestoga wagons, was used.

“A load of three or four tons required that the jack be sturdy and readily handled,” Mr. Omwake writes. Pictures of a number of these jacks are shown in his book, among them one particularly heavy, sturdy one dating back to 1766. “Generally these wagon jacks had two spurs in the base to prevent slipping, a wooden body, a riveted or keyed gear case, a ratchet wheel on the crank, a strong geared pillar with turntable two-spar top,” Mr. Omwake writes, then adds, “as they were very necessary to a team on the road, the owner’s name or initials were put on the top of the pilion, with the date.”

With a description of further details of the picture shown in this week’s column, this series on Conestoga wagons will close next week.